Yukon Quest

This article needs to be updated. (June 2023) |

The Yukon Quest, formally the Yukon Quest 1,000-mile International Sled Dog Race, is a sled dog race scheduled every February since 1984 between Fairbanks, Alaska, and Whitehorse, Yukon, switching directions each year. Because of the harsh winter conditions, difficult trail, and the limited support that competitors are allowed, it is considered the "most difficult sled dog race in the world",[1] or even the "toughest race in the world"[2]—"even tougher, more selective and less attention-seeking than the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race."[3] The originator envisioned it as "a race so rugged that only purists would participate."[3]

In the competition, first run in 1984, a dog team leader (called a musher) and a team of 6 to 14 dogs race for 10 to 20 days. The course follows the route of the historic 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, mail delivery, and transportation routes between Fairbanks, Dawson City, and Whitehorse. Mushers pack up to 250 pounds (113 kg) of equipment and provisions for themselves and their dogs to survive between checkpoints. Each musher must rely on a single sled for the entire run, versus three in the Iditarod.[3]

Ten checkpoints and four dog drops, some more than 200 miles (322 km) apart, lie along the trail. Veterinarians are present at each to ensure the health and welfare of the dogs, give advice, and provide veterinary care for dropped dogs; together with the race marshal or a race judge, they may remove a dog or team from the race for medical or other reasons. There are only nine checkpoints for rest, versus 22 in the Iditarod.[3] Mushers are permitted to leave dogs at checkpoints and dog drops, but not to replace them. Sleds may not be replaced (without penalty) and mushers cannot accept help from non-racers except at Dawson City, the halfway mark.

The route runs on frozen rivers, over four mountain ranges, and through isolated northern villages. Racers cover 1,016 miles (1,635 km) or more. Temperatures commonly drop as low as −60 °F (−51 °C), and winds can reach 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) at higher elevations. Because it begins a month earlier than the Iditarod, the Quest is a colder race, and is run on shorter solar days and through longer, darker nights.[3] Sonny Lindner won the inaugural race in 1984 from a field of 26 teams. The fastest run took place in 2010, when Hans Gatt finished after 9 days and 26 minutes. The 2012 competition had the closest one-two finish, as Hugh Neff beat Allen Moore by twenty-six seconds.

In 2005, Lance Mackey became the first Yukon Quest rookie to win the race, a feat that was repeated by 2011's champion, Dallas Seavey. In 2007, Mackey became the first to win both the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod, a feat he repeated the following year. The longest race time was in 1988, when Ty Halvorson took 20 days, 8 hours, and 29 minutes to finish. In 2000, Aliy Zirkle became the first woman to win the race, in 10 days, 22 hours, and 57 minutes. Yukon Quest International, which runs the Yukon Quest sled dog race, also runs two shorter races: the Junior Quest and the Yukon Quest 300 (previously the Yukon Quest 250).

The 2020 race finished on schedule despite the incipient COVID-19 pandemic, however the 2021 race was cancelled due to border closures and Covid protocols. In 2022, the US and Canadian sides separated to produce their own shorter versions of the races. To maintain a competitive format, the organizations adopted a multi-race format of different distances that ran along the portions of the trail on either side of the border. This format continued in 2023 and will be the same for the 2024 races. The Yukon Quest International Association (Canada) manages the Canadian side of the Yukon Quest.

History

[edit]The idea for the Yukon Quest originated in April 1983 during a bar-room discussion among four Alaskans: LeRoy Shank, Roger Williams, Ron Rosser, and William "Willy" Lipps.[4] The four proposed a thousand-mile sled dog race from Fairbanks, Alaska to Whitehorse, Yukon, to celebrate the Klondike Gold Rush-era mail and transportation routes between the two.[5] They disdained the many checkpoints and stages of the Iditarod Sled Dog Race[6] and envisioned an endurance race in which racers would rely on themselves and survival would be as important as speed.[7] "We wanted more of a Bush experience, a race that would put a little woodsmanship into it", Shank said at the race's 25th anniversary.[5]

This remained a vague plan until August 1983, when the first public organizational meetings took place.[5] Fundraising began, and the start date for the race was optimistically moved forward from February 1985 to February 25, 1984. The entry fee for the first race was $500, and Murray Clayton of Haines, Alaska became the first person to enter when he paid his fee in October 1983.[5] In December 1983, the race was officially named the Yukon Quest.[8] Two more months of planning followed, and a crew of volunteers was organized to staff the checkpoints and place trail markers.[5] On February 25, 1984, 26 racers left Fairbanks for Whitehorse.[9] Each team was limited to a maximum of 12 dogs, and racers had to finish with no fewer than nine. They also had to haul 25 pounds (11 kg) of food per dog (300 pounds (136 kg) total) to cover the long distances between checkpoints.[5]

Numerous problems occurred in the first race. The leading mushers had to break trail because the snowmobile intended for the task broke down. Trail markers often were absent or misplaced, and no preparations had been made for racers in Dawson City until organizer Roger Williams flew there shortly after the race began. After Dawson City, mushers had their dogs and sleds trucked 60 miles (97 km) to avoid a section of snowless trail, then had to deal with open sections of the Yukon River near Whitehorse due to above-average temperatures.[9] The eventual winner of the inaugural race, Sonny Lindner, was greeted with little fanfare on his arrival. On the race's 25th anniversary, he recalled, "I think it was 90 percent (camping) trip and maybe a little bit of racing."[9]

First decade

[edit]After the inaugural race, organizers improved the marking of the trail for the first contest held in the Whitehorse–Fairbanks direction. Musher Bill Cotter said, "The trail was so nice that it was difficult to keep from going too fast."[10] The race grew in popularity over the next few years. In 1988 and again in 1989, 47 mushers entered. In 1989, 31 completed the race—the most that have ever finished it.[11] In 1990, Connie and Terri Frerichs became the first (and so far only) mother and daughter to compete in the same Yukon Quest: Terri finished 21st, beating her mother (22nd) by 26 minutes.[12] The 1991 race saw eight teams withdraw in the first quarter because of an outbreak of a canine disease called the "Healy Virus". Thirty-five more dogs were sickened before the spread of the virus was halted by colder weather halfway through the race.[13] In 1992, unseasonable warmth caused problems in the first half of the race, and the second was affected by bitter cold.[14] The head veterinarian of that race, Jeannie Olson, was replaced after she offered canine acupuncture to several mushers. Though not then forbidden by any rule, this violated equal-treatment guidelines because she did not offer the treatment to every musher.[15] At the end of that race, George Cook became the first musher since 1984 to finish short of Whitehorse when open water on the Yukon River prevented him from continuing. Because he did not quit, race officials gave him the Red Lantern Award.[16]

Following the 1992 race, controversy erupted when the Alaska board of directors of Yukon Quest International informed the Yukon board that they were considering dropping the Yukon half of the Quest because Yukon officials did not meet fundraising goals. Alaska officials also believed it would be easier to manage an Alaska-only race.[17] A crisis was averted when the Yukon board of directors agreed to raise more money and the two sides formed a joint board of directors.[18] The 1993 race was run as usual, but Jeff Mann had a more eventful race than most. When a moose attacked his dog team, he was forced to kill it with an axe, then butcher it according to Quest rules. Later, he was penalized 90 minutes for borrowing a reporter's head lantern. Finally, after the conclusion of the race, he was fined half his winnings when his dogs tested positive for ibuprofen.[19]

In the 1994 race, Alaskan Bruce Cosgrove was denied entry by Canadian customs officials in the pre-race verification process, the only time a musher has been denied entry into either Canada or Alaska. Cosgrove started the race, but quit before the border.[20] Following the race, controversy again erupted when Alaska Yukon Quest officials announced they would unilaterally eliminate Whitehorse from the Yukon Quest and run a cheaper Fairbanks-to-Dawson City race. Members of the Yukon Quest organization revolted against this and voted to evict the board members who had proposed it.[18]

Second decade

[edit]The 1995 race featured 22 mushers, of whom 13 finished.[21] Budget problems caused the first prize to drop by 25% to $15,000, contributing to the low participation.[22] This problem was fixed for the 1996 race, with a first-place prize of $25,000.[22] The 1997 race was won by Rick Mackey, brother of later Quest winner Lance Mackey; the two are the only brother-brother winning tandem in Quest history.[23] Following the 1997 race, financial troubles again arose, this time on the Alaska side. Canadian organizers secured international sponsorship for the 1998 race, and when they refused to let this sponsorship money be used to pay debts accumulated in Alaska, members of the Alaska board threatened to host a separate competition. In the end, the Alaska board members were forced to resign, and a deal was worked out between the two sides.[24]

The 1998 race was run on schedule and had 38 entrants.[25] The 1999 race was won by Alaska Native Ramy Brooks, who defeated veterinarian Mark May by 10 minutes.[26] In 2000, Aliy Zirkle became the first woman to win the Yukon Quest after taking 10 days, 22 hours, and 57 minutes to trek the 1,000 miles (1,609 km).[27] Also in 2000, Yukon Quest International added two races: the Quest 250 (today the Quest 300) and the Junior Quest[28] (both described below). Competitors in each have gone on to participate in the Yukon Quest. The first of these graduated mushers competed in the 2001 race, won by Tim Osmar.[28]

In 2002, the Yukon Quest was won by Hans Gatt, an Austrian-born resident of British Columbia and the first European to win. This was the first of three consecutive wins, making him the first three-time winner.[29] In 2003, Gatt's second win was truncated by a lack of snow near Whitehorse. Unseasonable warmth forced organizers to truck mushers and their dog teams to Braeburn before continuing what became a 921 miles (1,482 km) competition.[30] The 2004 race saw 31 mushers start the race and 20 finish, a drop-out rate of 35%.[31] During the first 24 years of the competition, there were 776 starters and 513 finishers.[31] Though 90 more mushers attempted the race in the first 12 years than in the next dozen runnings, there is little difference in the percentage that did not finish (35% in 1984–1995; 33% in 1996–2007).[31]

Third decade

[edit]In 2005, first-time participant Lance Mackey broke Hans Gatt's three-win streak. Mackey finished in 11 days, 32 seconds.[32] The victory was the first of four straight wins by Mackey, who holds the record for most consecutive wins and is also the only four-time winner. During Mackey's second win, a fierce storm atop Eagle Summit caused a whiteout that forced seven mushers and dog teams to be evacuated by helicopter. Partly because of the storm, only 11 finished the 2006 race—the fewest ever.[33] The finishers also endured an unusual course: because snow was scarce near Whitehorse, they doubled back and finished in Dawson City after racing the 1,000 miles (1,609 km).[34] In 2007, three dogs were killed in unrelated incidents, but Mackey tied Gatt's record of three consecutive wins. One month later, Mackey became the first person to win both the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod in the same year.[35] Mackey's fourth win came during the 2008 race, the first Yukon Quest to end in Whitehorse since 2003.[34]

Because of the late 2000s recession, the 2009 Yukon Quest purse was reduced to $151,000 from a planned total of $200,000. As a result, the first prize was reduced to $30,000 from the planned $35,000.[36] Partly because of this, Mackey withdrew before the race, making it easier for a newcomer to win.[37] In the closest one–two finish, German Sebastian Schnuelle completed the race faster than anyone before, finishing that year's 1,016-mile (1,635 km) trip in 9 days, 23 hours, and 20 minutes. He was just four minutes ahead of Hugh Neff.[38]

Following the 2009 race, officials decided to advance the competition's start date by one week to better accommodate mushers also participating in the Iditarod. The 2010 race started in Fairbanks on February 6, 2010,[39] and the early start date was kept for the 2011 competition. Hans Gatt won the 2010 race with the fastest finish in Yukon Quest history: 9 days and 26 minutes.[40] That race was marked by good weather, and few mushers dropped out. In 2011, conditions returned to normal, as violent storms blasted the trail and mushers during the second half of the race. Only 13 of the 25 competitors completed the race, tying the record for fewest finishers.[41] In 2013, poor trail conditions over American Summit forced the Dawson to Eagle section of the course to be rerouted over the Yukon River.[42] Brent Sass became the race's third three-time winner in 2020, as the race finished on schedule despite the growing COVID-19 pandemic.[43] For 2021, race officials arranged to hold two separate races—one on the Canadian side of the border and the other on the Alaska side of the border—to abide by international quarantine. This plan was abandoned in September 2020 when the Canadian organizers canceled their race.[44] The American half of the 2021 race is still scheduled for February.

Route

[edit]

The course of the race varies slightly from year to year because of ice conditions on the Yukon River, snowfall, and other factors. The length of the route has also fluctuated, ranging from 921 miles (1,482 km)[30] in the weather-shortened 2003 race to 1,023 miles (1,646 km) in 1998.[45] In even-numbered years, the race starts in Fairbanks and ends in Whitehorse. In odd-numbered years, the start and finish lines switch.[46]

The route follows the Yukon River for much of its course and travels over four mountains: King Solomon's Dome, Eagle Summit, American Summit, and Rosebud Summit.[47] Its length is equivalent to the distance between England and Africa, and the distance between some checkpoints is the breadth of Ireland.[48] Racers endure ice, snow, and extreme cold. Wildlife is common on the trail, and participants sometimes face challenges from moose and wolves.[49][50] Because of the harsh conditions, the Yukon Quest has been called the "most difficult sled dog race in the world"[1] and the "toughest race in the world".[2][51]

Pre-race preparation

[edit]Iditarod has stiffer competition, but the Quest trail is vastly harder, it's not just the mountains. It's the Yukon River itself. Iditarod only has about a hundred and thirty miles on the Yukon, the Quest stays on the river closer to four hundred miles.

Because of the extreme difficulty of the competition, several stages of preparation are needed. The first is the food drop, when mushers and race officials position caches of food and supplies at race checkpoints.[52] This is necessary because mushers may only use their supplies along the route, reflecting the Gold Rush era, when dog trains would resupply at points along the trail.[53] One week after the food drop, all dogs participating in the race undergo a preliminary veterinarian inspection to ensure they are healthy enough to race 1,000 miles in subarctic conditions.[54] The final stage of formal preparation is two days before the race, when mushers pick their starting order from a hat.[55]

Whitehorse to Braeburn

[edit]

The modern start/finish in Whitehorse is at Shipyards Park,[56] but the traditional start took place near the former White Pass and Yukon Route train station, which today houses the Canadian offices of Yukon Quest International.[57] Shortly after leaving the starting line, racers follow the frozen Yukon River north out of town.[58] Crossing onto the Takhini River, mushers follow it north[59] to the Klondike-era Overland Trail. Racers take the trail to Braeburn Lodge, the first checkpoint.

This trail segment is about 100 miles (161 km) long.[47] The terrain consists of small hills and frequent frozen streams and lakes.[60] When the race runs from Fairbanks to Whitehorse, the Braeburn checkpoint is the site of a mandatory eight-hour stop to ensure the health of mushers' dogs before the final stage. In odd years, mushers must take a four-hour rest here or at Carmacks. The three minute start time difference is adjusted here. In even years, mushers must take an eight (8) hour rest here before continuing on for the last 100 miles (161 km) of the race.

Braeburn to Pelly Crossing

[edit]In the first leg of this, mushers must travel from Bareburn to Carmacks which is 39 miles (63 km). In odd years, mushers have the option of taking their four-hour rest here or at Bareburn. The three minute difference start time is also adjusted if the musher chooses to take their four-hour rest here.[47]

Coming out of Braeburn, competitors cross the Klondike Highway and proceed east for about 10 miles (16 km) to Coghlan Lake. From there they turn north, then northwest, and travel along a chain of lakes that stretches for about 30 miles (48 km).[61] They then enter a notorious stretch of heavily forested hills nicknamed "Pinball Alley"[62] for the way the rough terrain bounces sleds into trees, rocks, and other obstacles. Trees are so scarred from repeated sled impacts that they have lost their bark on one side.[63] In 1998, racer Brenda Mackey was jolted around so much by the rough trail that her sled became wedged between two trees, forcing her to cut one down to continue.[64]

After Pinball Alley, racers briefly mush along the Yukon River before climbing the riverbank to the Carmacks checkpoint.[65] They then follow a road for about 15 miles (24 km) and turn onto a firebreak trail. After departing the trail, they travel alongside and across the Yukon River to McCabe Creek, the first dog drop on the Whitehorse–Fairbanks route.[66] Leaving McCabe Creek, the race trail parallels a driveway and the Klondike Highway for several miles before turning north to cross the Pelly Burn, an area scorched by a wildfire in 1995.[67] Because the fire destroyed much of the forest in the area, this portion of the trail has few obstacles and is considered fast.[68] From the McCabe Creek site it is about 32 miles (51 km) to Pelly Crossing.[68]

Pelly Crossing to Dawson City

[edit]

The stretch between Pelly Crossing and Dawson City is the greatest distance between checkpoints of any sled dog competition in the world.[69] Between the two sites are 201 miles (323 km) of open trail, marked only by a dog drop at Scroggie Creek, an abandoned gold-mining site activated only during the Yukon Quest.[47]

From Pelly Crossing, mushers travel west on the frozen Pelly River, or on a road that parallels the river if ice conditions are poor. At Stepping Stone, shortly before the Pelly and Yukon rivers meet, they can rest at a hospitality stop before turning north.[70] From Stepping Stone to Scroggie Creek the trail consists of a mining road or "cat" road, named for the Caterpillar tracked mining vehicles that use it. Before organizers coordinated schedules with the mining equipment operators, racers often had to contend with heavy machinery blocking the trail or turning it into a muddy path.[71] The Scroggie Creek dog drop is at the confluence of the Stewart River and Scroggie Creek.[72]

After Scroggie Creek, the trail switches from a westerly direction to almost directly north. At this point, mushers enter the gold-mining district surrounding Dawson City. From the Stewart River adjacent to Scroggie, the trail climbs, crossing the Yukon Territory's Black Hills.[73] Fifty miles (80 km) from Dawson City and 55 miles (89 km) from Scroggie Creek, it crosses the Indian River, and mushers begin the climb to King Solomon's Dome, the highest point (4,002 feet (1,220 m)) on the trail.[73] The trail ascends more gradually in the Whitehorse–Fairbanks route than in the opposite direction, where mushers have to endure several switchbacks.[74] When mushers start in Whitehorse, they already have gained several thousand feet from the ascent into the Black Hills, including a climb over 3,550-foot (1,080 m) Eureka Dome.[75] The main difficulties come during the descent from King Solomon's Dome to Bonanza Creek, the epicenter of the Klondike Gold Rush.[76] After reaching the creek, mushers thread through an area of mining waste[77] and follow the Klondike River to Dawson City, the halfway point of the race. They are required to rest for 36 hours in Dawson City as a halfway-rest.[78]

Dawson City to Eagle

[edit]

The distance from Dawson City to Eagle, the first checkpoint in Alaska for the Whitehorse–Fairbanks route, is 144 miles (232 km).[47][79] Mushers must rest for four hours in Eagle.[80]

Racers exit Dawson City on the Yukon River and follow it for about 50 miles (80 km) to the Fortymile River hospitality stop.[73] The river's name comes from its distance from Fort Reliance, an abandoned trading post established in 1874.[81] From the hospitality stop, mushers travel southwest on the Fortymile River in what is one of the coldest portions of the race, because of cold air sinking to the bottom of the river valley.[82] The trail on the river crosses the United States–Canada border, noticeable only because of the border vista, a strip of land cleared of all foliage.[83] Shortly past the border, the river turns northwest, and mushers leave its frozen surface when it meets the Taylor Highway,[73] a road closed to automobile traffic during the winter. As the trail follows the highway for 49 miles (79 km) conditions are often hazardous, with high winds and drifting snow that can obscure trail markers. After climbing the 3,420-foot (1,040 m) American Summit,[47] the trail gradually descends 20 miles (32 km) to Eagle, on the banks of the Yukon River.[73]

Eagle to Central

[edit]

The route from Eagle to Central covers a distance of 233 miles (375 km).[47] In winter, Eagle is buffeted by high winds and drifting snow funneled through the town by nearby Eagle Bluff, which stands 300 feet (91 m) above the Yukon River.[84] Because it is the first stop in the United States, competitors are greeted at Eagle by a United States Department of Homeland Security official who checks passports and entry documents.[85]

After leaving Eagle, mushers travel northwest for 159 miles (256 km) on the Yukon River,[47] except for a few short portages.[73] During this stretch, two hospitality stops are available. The first is 28 miles (45 km) from Eagle at Trout Creek.[86] The next is Biederman's Cabin, the former home of Charlie Biederman, one of the last people to deliver mail by sled dog. (The final sled dog mail route was canceled in 1963, and Biederman's sled hangs in the National Postal Museum.)[87][88] A dog drop site is located 18 miles (29 km) from Biederman's Cabin at Slaven's Cabin, a historic site operated by the National Park Service.[89] Some 60 miles (97 km) past Slaven's Cabin mushers arrive in Circle,[90] so named because its founders believed it was on the Arctic Circle. (Circle is actually about 50 miles (80 km) south of that line.)[91]

From Circle, it is 74 miles (119 km) to the checkpoint in Central.[47] Mushers follow Birch Creek south until just before Circle Hot Springs. This area, along with the Fortymile stretch, is considered among the coldest on the trail, and mushers are advised to prepare for −60 °F (−51 °C) temperatures.[90] Turning west, they travel through frozen swamps before reaching the Steese Roadhouse checkpoint in Central.[92] In Central during even years, mushers have the option of taking their four-hour rest here or at Mile 101. If they choose to, the three minute start difference will be subtracted from their rest time.[93]

Central to Two Rivers

[edit]

From Central to the final (or first, in the Fairbanks–Whitehorse direction) checkpoint in Two Rivers is 114 miles (183 km).[47] Despite the comparative closeness of the checkpoints and the location of a dog drop between them, this is considered the most difficult stretch of dog sled trail in the world.[94] At this point, mushers must climb the two steepest and most difficult mountains on the trail: Eagle Summit and Rosebud Summit.[47]

After leaving Central, mushers head west, paralleling the Steese Highway, which connects Central and Circle with Fairbanks. The trail travels through frozen swamps, mining areas, and firebreaks for about 20 miles (32 km). Mushers then encounter the Steese Highway for a second time before crossing several creeks to begin the ascent of Eagle Summit.[90] They eventually climb above the tree line and are exposed to the wind as they continue upward. The weather atop Eagle Summit is harsh as this is a convergence zone between the Yukon Flats to the north and the low ground of the Tanana Valley to the south. A differential in the weather within the two valleys causes high winds and precipitation when there is moisture in the atmosphere.[95] The final few hundred yards of the climb consists of a 30-degree slope often scoured to bare rock and tundra by the fierce wind.[96] The crossing point itself is a symmetrical saddle, with two peaks of similar height separated by 100 yards (91 m).[97] The south side of Eagle Summit is not as steep, and mushers generally have an easier time reaching the checkpoint at Mile 101.[90] When descending the steep northern slope of Eagle Summit on the Fairbanks–Whitehorse route, many mushers wrap their sled runners in chains to increase friction and slow the plunge.[98]

The Mile 101 checkpoint is a cabin at mile marker 101 (the distance from Fairbanks) on the Steese Highway. At Mile 101, mushers have the option of taking their four-hour rest during even years. They can also take the rest at Central during even years. Again, the three minute start difference will be subtracted from the race if the musher desires to take their rest here. The cabin gives mushers the opportunity for a short rest between Eagle Summit and Rosebud Summit.[99] The ascent of Rosebud Summit begins about 10 miles (16 km) south of the dog drop. It consists of a gradual climb of 5 miles (8.0 km) followed by a steep descent into the valley that contains the north fork of the Chena River. The descent also brings mushers back into forested terrain.[100] The trail then parallels a road for about 27 miles (43 km) before entering the final checkpoint at Twin Bears Campground near Two Rivers.[90]

Two Rivers to Fairbanks

[edit]

Two Rivers is the final checkpoint in the Whitehorse–Fairbanks route. Mushers are required to rest at least eight hours in Two Rivers in odd years to ensure the health of their dogs during the final leg of the race. The terrain in this stretch is among the easiest on the trail, with gently rolling hills and forest which gradually change into an urban landscape as racers approach Fairbanks.[101] The greatest challenge for racers in the Two Rivers area is distinguishing the Yukon Quest trail from other sled dog trails, many of which have similar markings.[102] Mushers have occasionally been deceived by these markings and taken wrong turns.[101][103]

Beyond Two Rivers, the trail reaches the Chena River northwest of Fairbanks. This is the final stretch, and mushers use the river to enter Fairbanks and reach the finish line,[104] which is on the river itself in the middle of downtown Fairbanks. Regardless of the timing of the finish, several thousand spectators typically gather to watch the first musher cross the finish line.[104]

Route changes

[edit]The 1984 route was slightly different from today's. It had just one non-checkpoint dog drop, at the Mile 101 location,[105] and bypassed American Summit, Pelly Junction, and Braeburn. Instead of running through Braeburn, mushers traveled across Lake Laberge for 60 miles (97 km) between Whitehorse and Minto.[106] The inaugural race also included a checkpoint at Chena Hot Springs Resort near Fairbanks. This site was moved to nearby Angel Creek after mushers complained that the hot springs melted nearby snow, causing their dogs to become wet—an extreme hazard in sub-freezing temperatures.[107] Two additional dog drops were added for the 1994 race: Biederman's Cabin (since replaced by Slaven's Cabin) and McCabe Creek.[105] In 1995, the Whitehorse end of the trail was moved away from Lake Laberge to near the Takhini River.[108] Additional changes that year included the rerouting of the trail around the southern and eastern sides of King Solomon's Dome south of Dawson City[109] and the introduction of the Scroggie Creek dog drop site on the shore of the Stewart River.[105]

In 1996, the trail was rerouted through Pelly Crossing and a checkpoint was added there, and the Lake Laberge stretch was replaced by a route through Braeburn and along the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail.[109] In 1997, mushers were routed through the Chena River Lakes Flood Control Project and to the Alaska town of North Pole before continuing on to Fairbanks.[110] The North Pole loop was removed before the 2009 race, and mushers were directed through Two Rivers instead.[111] Starting in the 2010 race, the Mile 101 location was upgraded from a dog drop to a full-fledged checkpoint. In the past several races, the Two Rivers checkpoint has changed locations annually: from a lodge to a campground, and then to a gravel pit in 2011.

Weather

[edit]The Yukon Quest trail is in the subarctic climate range. In Fairbanks, the average February temperature is −3.8 °F (−20 °C), but −40 °F (−40 °C) is not uncommon, and temperatures have dropped to −58 °F (−50 °C).[112] An average of 7.3 inches (185 mm) of snow falls in February, with average snowpack depth of 22 inches (559 mm).[112]

Outside the sheltered urban areas of Fairbanks, Whitehorse, and Dawson City, temperatures and snowfall are often more extreme. During the 2008 race, competitors started in −40 °F (−40 °C) temperatures in Fairbanks and then faced winds of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) on the trail, resulting in severe wind chills.[113] At higher elevations, such as the crossings of Rosebud and Eagle summits, whiteout blizzards are common. In the 2006 race, 12 teams were struck by a massive storm that eventually caused the evacuation of seven teams by helicopter.[114][115][116] In 2009, mushers endured winds up to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h), blowing snow, and subzero temperatures atop Eagle Summit,[117] where conditions had been even worse in a storm during the 1988 race, when wind chill temperatures dropped below −100 °F (−73 °C).[118]

The extreme temperatures pose a serious health hazard. Frostbite is common, as is hypothermia. In the 1988 Yukon Quest, Jeff King suffered an entirely frozen hand because of nerve damage from an earlier injury which left him unable to feel the cold. King said his hand became "like something from a frozen corpse".[119] In 1989, King and his team drove through a break in the Yukon River in −38 °F (−39 °C) temperatures. Frozen by the extreme cold, King managed to reach a cabin and thaw out.[120] Other racers have suffered permanent damage from the cold: Lance Mackey suffered frostbitten feet during the 2008 Yukon Quest,[121] and Hugh Neff lost the tips of several toes in the 2004 race.[122]

Participants

[edit]

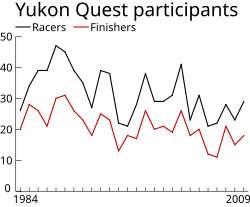

Since the race's inception in 1984, 353 people from 11 countries have competed in the Yukon Quest, some many times. The race attracts from 21 (in 1996)[123] to 47 (in 1988 and 1989)[11] mushers each year. Of the 776 entries from 1984 to 2007, 263 (34%) did not finish.[31] The racers have come from various professions: taxicab drivers, swimming instructors, coal miners, tax assessors, lawyers, fur trappers, journalists, and a car salesman have all entered.[11]

At the end of the competition, racers are given awards for feats performed on the trail. The foremost is the championship award, given to the winner. Accompanying this is the Golden Harness Award, given to the winner's two lead sled dogs.[124] The next award is the Veterinarians Choice Award, which is voted on by race veterinarians and given to the musher who took the best care of their dogs during the race.[124] Other awards include the Challenge of the North Award—given to the musher who "exemplifies the spirit of the Yukon Quest"—and the Sportsmanship Award, given to the most sportsmanlike competitor, as chosen by a vote of the mushers.[124]

The Rookie of the Year Award is given to the highest-finishing first-time competitor. The Dawson Award, consisting of four ounces of gold, is given to the first musher to reach Dawson City (the midpoint) who also finishes the competition.[124] The final award is the Red Lantern, given to the last official finisher of the year's race.[124] Two awards have been discontinued: the Kiwanis Award, given to the first musher to cross the Alaska–Yukon border, and the Mayor's Award, given to the Yukon Quest champion by the Mayor of Fairbanks.[124]

The 2011 Yukon Quest champion is Alaskan Dallas Seavey, who finished the race in 10 days, 11 hours and 53 minutes. Seavey, who has run the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race several times, won the Yukon Quest in his rookie year and therefore also was named rookie of the year.[125] Haliburton, Ontario musher Hank DeBruin won the 2011 Red Lantern Award by finishing the race in 13 days, 10 hours, and 54 minutes.[126] For the first time in Yukon Quest history, more than one musher received the sportsmanship award. Following the 2011 race, Allen Moore, Brent Sass and Mike Ellis shared the honor. Ken Anderson, who reached Dawson City third, was the only one of the top three at that point to finish, and thus received the Dawson Award. Wasilla musher Kelley Griffin received the Spirit of the North award, and the Veterinarian's Choice award was given to Mike Ellis and his wife/handler Sue Ellis.[127]

Dogs

[edit]

Dogs in the Yukon Quest come in a variety of sizes and breeds, though the most common are Alaskan and Siberian Huskies weighing between 45 and 70 pounds (20 and 32 kg).[128] The Alaskan Husky is not a recognized breed, but an amalgam of several different types bred for speed, stamina, and strength.[129] Siberian Huskies are a breed recognized by the American Kennel Club and are characterized by thick coats, stiff ears, a fox-like tail, and medium size.[130] Siberian Huskies are typically larger and slower than their Alaskan counterparts,[131] causing mushers to nickname the breed "Slowberians",[132] but have more pulling power. The difference was seen during the 1998 Yukon Quest, when Bruce Lee's team of Alaskan Huskies competed against André Nadeau's team of Siberians. Lee's team was faster than Nadeau's over short stretches, but Lee had to rest more often. Nadeau had a head start out of the final checkpoint, but Lee was able to overtake him.[133]

Rules

[edit]The Yukon Quest encourages participants' self-sufficiency,[7] and one of its objectives is "[to] encourage and facilitate knowledge and application of the widest variety of bush skills and practices that form the foundation of Arctic survival."[134] On the trail, racers may not accept outside assistance and are limited in the changes they may make to their teams and sled.[135] There are 10 checkpoints and four additional locations where sick or injured dogs may be dropped from a team. Only four checkpoint stops are mandated: a 36-hour stop at Dawson City; a four-hour stop in Eagle, Alaska; a two-hour stop at the first checkpoint; and an eight-hour stop at the last.[136]

As well as food, camping equipment, and dog-care gear, mushers must carry an axe, a cold-weather sleeping bag, a pair of snowshoes, veterinary records, Quest promotional material, a cooker, and eight booties per dog.[137] Included in the required promotional material are numerous event covers intended to reflect the Quest's ancestry as a mail route.[138] One unusual rule requires mushers to immediately butcher any game animal killed during the race. This rule was applied in 1993, when a musher was attacked by a moose and killed it to protect himself.[137]

Entry requirements

[edit]Competitors must meet a series of written and unwritten requirements before entering. The first is that each musher must have a team of dogs. The race does not furnish any dogs, but participants have been known to lease or borrow dog teams rather than raise their own. In the 2009 Yukon Quest, for example, Newton Marshall from the Jamaica Dogsled Team borrowed a dog team from Canadian Hans Gatt.[139] Each competitor must have completed at least two sled dog races sanctioned by Yukon Quest International: one of 200 miles (320 km) and one of 300 miles (480 km).[140] Sanctioned races include the Copper Basin 300 and the Tustumena 200, Alaska races held before the Quest.[141][142]

Those who have completed at least 500 miles (805 km) of Quest-sanctioned racing are eligible to send in an entry form. This requires entrants to certify that they are older than 18, have not been censured by the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, and have never been convicted of animal abuse or neglect.[140] They must pay $1,500 or $2,000 for late entries.[140]

Dog health

[edit]

Many of the Quest's rules are intended to ensure the health of dogs in hazardous conditions. This process begins before the race, when all dogs must be examined by race veterinarians, who certify that the animals are suited and healthy enough to participate.[54] Before the race, dog equipment also must be checked by race officials. Padded harnesses are required, each musher must carry an appropriate amount of food, and additional food supplies must be in position at checkpoints.[135]

Mushers must start the race with at most fourteen dogs and finish with no fewer than six in harness (additional dogs may be carried in the sled basket).[135] Dogs are visually examined by veterinarians stationed at every checkpoint, and mushers can be ejected and banned from the race for mistreating dogs. Dog whips and forced feeding are forbidden.[143] Participating dogs may not receive injections during the race or be under the influence of performance-enhancing substances such as steroids. The race marshal may remove any team from the race for violations of these rules or substandard dog care.[143]

Organization officials and race veterinarians award one team each year with the Humanitarian Award for exemplary dog care. In 2023 the team of Amanda Otto, who placed second, was in such good condition at the end of the race, still yelping and pulling, that she was awarded in the first unanimous decision in race history.[144]

Penalties

[edit]The Yukon Quest's rules allow race officials latitude on whether to assess a time penalty or monetary fine on mushers who violate one or more regulations.[145] The most serious penalties can be assessed for mistreating dogs. Racers have been forcibly removed from the race for inadequate dog care; the most recent instance of this took place in 2008, when Donald Smidt was removed.[146] More common are minor time and monetary penalties. For example, Dan Kaduce was fined $500 of his eventual $9,000 winnings for missing roll call at a mandatory meeting in 2007. Fines of $500 also have been levied for not attending the finish banquet, littering, not wearing start and finish bibs, or losing veterinary records.[137] These minor penalties can have an effect on the race. In 2009, Hugh Neff, then in second place, was penalized two hours for mushing on the Circle Hot Springs road.[147] As a result, he finished four minutes behind Sebastian Schnuelle, the winner.[38]

Junior Yukon Quest and Yukon Quest 300

[edit]In addition to the main 1,000-mile sled dog race, the Yukon Quest organization operates two shorter races: the Junior Yukon Quest and the Yukon Quest 300.[148] The two began in 2000, though in its first three years the Quest 300 was only 250 miles and thus known as the Quest 250.[28]

Junior Yukon Quest

[edit]The Junior Yukon Quest, or Junior Quest, is a 135-mile (217 km) race for mushers older than 14 but under 18.[149] Unlike the Yukon Quest, the Junior Quest does not change locations and always starts and ends in Fairbanks.[28] It is billed as an opportunity for young racers to experience a mid-distance sled dog race. They must plan a food drop, camp away from checkpoints, and carry much of the same equipment as mushers in the Yukon Quest and Yukon Quest 300.[148]

Yukon Quest 300

[edit]The Yukon Quest 300 is a 300-mile (480 km) race along the regular Yukon Quest trail. It alternates starting locations along with the main race and is intended for less-experienced mushers training for longer races. The race is also a qualifier for the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race and the following year's Yukon Quest. Several mushers, including Fort Yukon Native Josh Cadzow, have used the race as a trial before entering the longer races.[150][151]

In 2009, the race was capped at 25 entries.[152] When the Quest 300 starts in Whitehorse, its course follows the main Yukon Quest trail until the Stepping Stone hospitality stop. From there, it turns southwest, ending in Minto Landing, Yukon.[152] The Fairbanks route follows the main trail to Circle, then reverses course, ending in Central.[152]

See also

[edit]- American Dog Derby

- Carting

- Finnmarksløpet (Norway)

- Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race (Alaska)

- La Grande Odyssée (France and Switzerland)

- List of sled dog races

- Yukon Arctic Ultra

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences. "Arctic Zirkle", Penn Arts & Sciences Magazine. Fall 2001. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Balzar, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e Joyal, Brad. "There's a sled dog race tougher than the Iditarod, and a 78-year-old crazy enough to try it". The Washington Post. No. February 24, 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Yukon Quest International. "Yukon Quest race history" Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Saari, Matias. "Founders recall origins of the Yukon Quest" Archived 2009-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 22, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 248

- ^ a b Firth, p. 28

- ^ Staff report. "Looking back in Fairbanks — Dec. 22"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. December 22, 2008. Accessed May 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Saari, Matias. "1984" Archived 2009-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 22, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1985" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c Saari, Matias. "1989" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1990" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 196

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1992" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Firth, pp. 199–200

- ^ Firth, p. 201

- ^ Firth, p. 234

- ^ a b Firth, p. 235

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1993" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 207

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1995" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Firth, p. 265

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1997" Archived 2009-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 236

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1998" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1999" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "2000" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Saari, Matias. "2001" Archived 2009-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "2002" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Saari, Matias. "2003" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Saari, Matias. "2004" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "2005" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 28, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "2006" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Saari, Matias. "Mackey wins his fourth Yukon Quest by a nose" Archived 2008-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 20, 2008. Accessed February 28, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "2007" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed February 28, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Lead Yukon Quest mushers reach Braeburn by end of first day"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 15, 2009. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- ^ Staff Report. "Mackey officially withdraws from Yukon Quest"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. January 24, 2009. Accessed February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Saari, Matias. "Schnuelle sets record in Yukon Quest win; Neff only 4 minutes behind"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 24, 2009. Accessed February 24, 2009.

- ^ The Associated Press. "Yukon Quest plans earlier start date in 2010" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. August 6, 2009. Accessed March 6, 2011.

- ^ Armstrong, Joshua. "Gatt claims fourth Yukon Quest championship in record time", Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 15, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2011. Archived March 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Caldwell, Suzanna. "And the winner of the 2011 Yukon Quest is ..." Archived 2012-07-12 at archive.today , Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 14, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Richardson, Jeff (3 February 2013). "Home Sports Yukon Quest - Yukon Quest officials reroute section of race trail". Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Hopkins-Hill, John (11 February 2020). "Brent Sass wins the 2020 Yukon Quest". Yukon News. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Bragg, Beth (4 September 2020). "Pandemic takes Yukon out of the 2021 Yukon Quest sled dog race". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Balzar, p. 3

- ^ Balzar, p. 5

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Yukon Quest International. "Yukon Quest trail map/trail elevations" Archived 2014-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed March 3, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 7

- ^ Killick, p. 10

- ^ Firth, p. 209

- ^ Killick, pp. 7–8

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Quest mushers put strategy into food, staple planning"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 1, 2009. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- ^ Balzar, p. 56

- ^ a b Saari, Matias. "Most dogs get the go-ahead at Yukon Quest vet check"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 8, 2009. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Yukon Quest rookies stay positive after drawing starting positions"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 13, 2009. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- ^ "2020 Yukon Quest Events" (PDF). Yukon Quest. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Killick, p. 16

- ^ Killick, p. 55

- ^ Killick, p. 56

- ^ Killick, pp. 57–58

- ^ Killick, p. 80

- ^ Yukon Quest International. "Majority of mushers have reached Carmacks" Archived 2012-02-20 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. February 12, 2007. Accessed March 10, 2009.

- ^ Killick, p. 81

- ^ Balzar, p. 69.

- ^ Killick, p. 97

- ^ Killick, p. 106

- ^ Killick, p. 112

- ^ a b Schandelmeier, p. 2

- ^ Killick, p. 132

- ^ Killick, p. 133

- ^ Firth, pp. 140–144

- ^ Killick, pp. 140–141

- ^ a b c d e f Schandelmeier, p. 3

- ^ Killick, pp. 147–148

- ^ O'Donoghue, p. 116

- ^ Killick, p. 148

- ^ O'Donoghue, pp. 136–137

- ^ Killick, p. 153

- ^ Killick, p. 168

- ^ "The Race in Action". Yukon Quest. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ^ Killick, p. 173

- ^ Killick, p. 186

- ^ Killick, p. 192

- ^ Killick, pp. 195–196

- ^ Killick, p. 195

- ^ Killick, p. 217

- ^ Balzar, p. 170

- ^ Killick, p. 225

- ^ Killick, p. 229

- ^ a b c d e Schandelmeier, p. 4

- ^ Killick, p. 233

- ^ Killick, p. 238

- ^ "Yukon Quest Trail". Yukon Quest. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ^ Killick, p. 246

- ^ Balzar, p. 253

- ^ Balzar, pp. 252–254

- ^ Killick, pp. 246–247

- ^ Killick, p. 249

- ^ Killick, p. 254

- ^ Killick, p. 256

- ^ a b Killick, p. 261

- ^ Balzar, p. 276

- ^ O'Donoghue, p. 312

- ^ a b Killick, p. 262

- ^ a b c Firth, p. 237

- ^ Firth, p. 279

- ^ Firth, p. 19

- ^ Firth, pp. 237–238

- ^ a b Firth, p. 238

- ^ Firth, p. 240

- ^ Willomitzer, Gerry. "Tuesday morning update" Archived 2012-02-20 at the Wayback Machine, Yukon Quest International. February 24, 2009. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Alaska Climate Research Center. "Climatological data: Fairbanks International Airport" Archived 2013-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, climate.gi.alaska.edu. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Quest trail fraught with difficulties" Archived 2007-04-23 at archive.today , Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 8, 2008. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ C. Talbott. "Mushers recount summit adventures" Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 15, 2006. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Eagle Summit is more merciful this time around"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 11, 2008. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Crossing of Eagle Summit brings back memories for mushers", Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 12, 2008. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Troubles on Eagle Summit drop William Kleedehn from Yukon Quest lead" Archived 2009-02-27 at archive.today, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 24, 2009. Accessed February 25, 2009.

- ^ Firth, p. 39

- ^ Jenkins, p. 195

- ^ Jenkins, pp. 195–204

- ^ Medred, Craig. "Mackey proves Iditarod/Quest wins no fluke" Archived 2009-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, Anchorage Daily News. March 12, 2008. Accessed August 3, 2009.

- ^ Cremata, Andrew. "'Dream Quest' for Dyea dogs" Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine , Skagway News. February 11, 2005. Accessed August 3, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "1996" Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 6, 2008. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Yukon Quest International. "Musher hall of fame" Archived 2013-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- ^ Caldwell, Suzanna. "Rookie mushing progeny Dallas Seavey wins 2011 Yukon Quest" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 16, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Caldwell, Suzanna. "Red Lantern winner, Quest musher Hank DeBruin makes it to Fairbanks", Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 19, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011. Archived March 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Caldwell, Suzanna. "Yukon Quest honors its contestants at banquet", Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Retrieved March 6, 2011. Archived March 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yukon Quest International. "The modern sled dog" Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed March 11, 2009.

- ^ WNET. "Sled dogs: An Alaskan epic", PBS.org. Accessed March 11, 2009.

- ^ American Kennel Club, Inc. "AKC meet the breeds: Siberian husky", AKC.org. Accessed March 11, 2009.

- ^ Killick, p. 74

- ^ Balzar, p. 110

- ^ Killick, p. 255

- ^ Yukon Quest International. "Mission statement and philosophy" Archived 2010-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed February 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c 2009 Yukon Quest Rules, p. 6

- ^ 2009 Yukon Quest Rules, p. 5

- ^ a b c Saari, Matias. "Yukon Quest rules range from the practical to the peculiar" Archived 2009-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 14, 2009. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Moran, Tom. "Leaving a stamp on the Quest" Archived 2008-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 10, 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Jamaican musher prepares for Yukon Quest", Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 12, 2009. Accessed May 21, 2009. Archived April 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c 2009 Yukon Quest Rules, p. 1.

- ^ Copper Basin 300, Inc. "Copper Basin 300 Sled Dog Race", cb300.com. Accessed May 21, 2009.

- ^ Tustumena 200. "Tustumena 200 Alaska Dog Sled Race", tustumena200.com. May 11, 2009. Accessed May 21, 2009.

- ^ a b 2009 Yukon Quest Rules, p. 7

- ^ "Sass Wins, Otto Surprise Second". KUAC-TV. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- ^ 2009 Yukon Quest Rules, p. 2

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Quest legend Turner scratches, leaving 22 mushers competing"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 11, 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Second-place Yukon Quest musher Hugh Neff is penalized two hours" Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 23, 2009. Accessed February 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Yukon Quest International. "Other Yukon Quest races" Archived 2013-07-02 at the Wayback Machine, Yukonquest.com. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Staff Report. "Six mushers set to race in Jr. Quest"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 7, 2009. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Prepping for the big race to come" Archived 2007-04-23 at archive.today , Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 12, 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ Saari, Matias. "Crispin Studer takes first in Quest 300"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. February 18, 2009. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- ^ a b c Saari, Matias. "Mushers quickly fill Yukon Quest 300"[permanent dead link], Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. October 29, 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.

References

[edit]- Balzar, John. Yukon Alone: The World's Toughest Adventure Race. New York: Henry Holt, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8050-5950-2. Also titled The Lure of the Quest: One Man's Story of the 1025-mile Dog-sled Race across North America's Frozen Wastes. London: Headline, 2000. ISBN 0-7472-7145-3.

- Firth, John. Yukon Quest: The 1,000-Mile Dog Sled Race Through the Yukon and Alaska. Whitehorse, Yukon: Lost Moose Publishing, 1998. ISBN 978-1-896758-03-9.

- Jenkins, Peter. Looking For Alaska. New York: St Martin's, 2001. ISBN 0-312-26178-0.

- Killick, Adam. Racing the White Silence: On the Trail of the Yukon Quest. Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2005. ISBN 978-0-14-100373-3.

- O'Donoghue, Brian Patrick. Honest Dogs: A Story of Triumph and Regret from the World's Toughest Sled Dog Race. Kenmore, Wash.: Epicenter Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-945397-78-6.

- Schandelmeier, John. 2009 Guide to the Yukon Quest Trail (PDF), Yukonquest.com. Accessed March 13, 2009.

- Yukon Quest International. 2009 Yukon Quest Rules (PDF), Yukonquest.com. Accessed February 22, 2009.

Further information

[edit]- Berton, Pierre. The Klondike Quest: A Photographic Essay 1897-1899. North York, Ont.: Boston Mills, 2005. ISBN 978-1-55046-453-5.

- Cook, Ann Mariah. Running North: A Yukon Adventure. Chapel Hill. N.C.: Algonquin Books, 1998. ISBN 978-1-56512-253-6.

- Dick, Laurent. Yukon Quest Photo Journey. Anchorage, Alaska: Todd Communications, 2003. ISBN 978-1-57833-219-9.

- Evans, Polly. Mad Dogs and an Englishwoman: Travels with Sled Dogs in Canada's Frozen North. New York: Delta, 2009. ISBN 978-0-385-34111-0.

- Phillips, Michelle. My Yukon Quest Story: 1000 Mile Sled Dog Journal. Tagish, Yukon: Michelle Phillips, 2003. ISBN 0-9669553-0-7.

- Proudfoot, Shannon (March 26, 2012). "Yukon Quest is hell frozen over". Sportsnet Magazine. Toronto: Rogers Media.

- Stuck, Hudson. Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled: A Narrative of Winter Travel in Interior Alaska. 2nd ed. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. (Here [1] at Project Gutenberg.)

Fiction

[edit]- Browne, Belmore. The Quest of the Golden Valley: A Story of Adventure on the Yukon. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1916.

- Henry, Sue. Murder on the Yukon Quest. New York: Avon, 2000. ISBN 978-0-380-78864-4.

Video

[edit]- Bristow, Becky. Dog Gone Addiction. Wild Soul Creations, 2007. 67 minutes.

- CBC North Television. The Lone Trail: The Dogs and Drivers of the Yukon Quest. CBC, 2004. 60 minutes.

- Morner, Dan and Schuerfeld, Sven. 6ON-6OFF. Morni Films, 2005. 63 minutes.

- Northern Light Media. Mark Hegener, dir. Appetite and Attitude: A conversation with Lance Mackey. 46 minutes.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the Yukon Quest

- Yukon Quest at Fairbanks Daily News-Miner