South Korea

Republic of Korea | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: 애국가 Aegukga "The Patriotic Song" | |

National seal: | |

Territory controlled

Territory claimed but not controlled (North Korea) | |

| Capital and largest city | Seoul 37°33′N 126°58′E / 37.550°N 126.967°E |

| Administrative center | Sejong City[a] 36°29′13″N 127°16′56″E / 36.487002°N 127.282234°E |

| Official languages | Korean (Pyojuneo) Korean Sign Language[1] |

| Official script | Hangul |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[2] | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Yoon Suk Yeol | |

| Han Duck-soo | |

| Woo Won-shik | |

| Cho Hee-dae | |

| Lee Jong-seok | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Establishment history | |

• Gojoseon | October 3, 2333 BCE (mythological) |

| 57 BCE | |

| 668 | |

| July 25, 918 | |

| August 13, 1392 | |

| October 12, 1897 | |

| August 22, 1910 | |

| March 1, 1919 | |

| 11 April 1919 | |

| August 15, 1945 | |

• US administration of Korea south of the 38th parallel | September 8, 1945 |

| August 15, 1948 | |

| February 25, 1988 | |

| Area | |

• Excl. North Korea | 100,363[5][6][7] km2 (38,750 sq mi) (107th) |

• Water (%) | 0.3 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 507/km2 (1,313.1/sq mi) (15th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (19th) |

| Currency | South Korean won (₩) (KRW) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Korea Standard Time) |

| Date format |

|

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +82 |

| ISO 3166 code | KR |

| Internet TLD | |

South Korea,[c] officially the Republic of Korea (ROK),[d] is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone; though it also claims the land border with China and Russia.[e] The country's western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eastern border is defined by the Sea of Japan. South Korea claims to be the sole legitimate government of the entire peninsula and adjacent islands. It has a population of 51.96 million, of which half live in the Seoul Capital Area, the ninth most populous metropolitan area in the world. Other major cities include Busan, Daegu, and Incheon.

The Korean Peninsula was inhabited as early as the Lower Paleolithic period. Its first kingdom was noted in Chinese records in the early 7th century BCE. After the unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea into Silla and Balhae in the late 7th century, Korea was ruled by the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) and the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897). The succeeding Korean Empire (1897–1910) was annexed in 1910 into the Empire of Japan. Japanese rule ended following Japan's surrender in World War II, after which Korea was divided into two zones: a northern zone, which was occupied by the Soviet Union, and a southern zone, which was occupied by the United States. After negotiations on reunification failed, the southern zone became the Republic of Korea in August 1948, while the northern zone became the communist Democratic People's Republic of Korea the following month.

In 1950, a North Korean invasion began the Korean War, which ended in 1953 after extensive fighting involving the American-led United Nations Command and the People's Volunteer Army from China with Soviet assistance. The war left 3 million Koreans dead and the economy in ruins. The authoritarian First Republic of Korea led by Syngman Rhee was overthrown in the April Revolution of 1960. However, the Second Republic failed to control the revolutionary fervor. The May 16 coup of 1961 led by Park Chung Hee put an end to the Second Republic, signaling the start of the Third Republic in 1963. South Korea's devastated economy began to soar under Park's leadership, recording one of the fastest rises in average GDP per capita. Despite lacking natural resources, the nation rapidly developed to become one of the Four Asian Tigers based on international trade and economic globalization, integrating itself within the world economy with export-oriented industrialization. The Fourth Republic was established after the October Restoration of 1972, in which Park wielded absolute power. The Yushin Constitution declared that the president could suspend basic human rights and appoint a third of the parliament. Suppression of the opposition and human rights abuse by the government became more severe in this period. Even after Park's assassination in 1979, the authoritarian rule continued in the Fifth Republic led by Chun Doo-hwan, which violently seized power by two coups and brutally suppressed the Gwangju Uprising. The June Democratic Struggle of 1987 ended authoritarian rule, forming the current Sixth Republic. The country is now considered among the most advanced democracies in continental and East Asia.

South Korea maintains a unitary presidential republic under the 1987 constitution with a unicameral legislature, the National Assembly. It is considered a regional power and a developed country, with its economy ranked as the world's fourteenth-largest by nominal GDP and the fourteenth-largest by PPP-adjusted GDP. Its citizens enjoy one of the world's fastest Internet connection speeds and densest high-speed railway networks. The country is the world's ninth-largest exporter and ninth-largest importer. Its armed forces are ranked as one of the world's strongest militaries, with the world's second-largest standing army by military and paramilitary personnel. In the 21st century, South Korea has been renowned for its globally influential pop culture, particularly in music, TV dramas, and cinema, a phenomenon referred to as the Korean Wave. It is a member of the OECD's Development Assistance Committee, the G20, the IPEF, and the Paris Club.

Etymology

The name Korea is an exonym, although it was derived from a historical kingdom name, Goryeo (Revised Romanization) or Koryŏ (McCune–Reischauer). Goryeo was the shortened name officially adopted by Goguryeo in the 5th century[11][12][13] and the name of its 10th-century successor state Goryeo.[14][15] Visiting Arab and Persian merchants pronounced its name as "Korea".[16] The modern name of Korea appears in the first Portuguese maps of 1568 by João vaz Dourado as Conrai[17] and later in the late 16th century and early 17th century as Corea (Korea) in the maps of Teixeira Albernaz of 1630.[18]

The Kingdom of Goryeo became first known to Westerners when Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca in 1511 and described the peoples who traded with this part of the world known by the Portuguese as the Gores.[19] Despite the coexistence of the spellings Corea and Korea in 19th-century publications, some Koreans believe that Imperial Japan, around the time of the Japanese occupation, intentionally standardized the spelling of Korea, making Japan appear first alphabetically.[20][21]

After Goryeo was replaced by Joseon in 1392, Joseon became the official name for the entire territory, though it was not universally accepted. The new official name has its origin in the ancient kingdom of Gojoseon (2333 BCE). In 1897, the Joseon dynasty changed the country's official name from Joseon to Daehan Jeguk (Korean Empire). The name Daehan (Great Han) derives from Samhan (Three Han), referring to the Three Kingdoms of Korea, not the ancient confederacies in the southern Korean Peninsula.[22][23] However, the name Joseon was still widely used by Koreans to refer to their country, though it was no longer the official name. Under Japanese rule, the two names Han and Joseon coexisted.

Following the surrender of Japan, in 1945, the "Republic of Korea" was adopted as the legal English name for the new country. However, it is not a direct translation of the Korean name.[24] As a result, the Korean name "Daehan Minguk" is sometimes used by South Koreans as a metonym to refer to the Korean ethnicity (or "race") as a whole, rather than just the South Korean state.[25][24]

History

Ancient Korea

The Korean Peninsula was inhabited as early as the Lower Paleolithic period.[27][28]

According to Korea's founding mythology, the history of Korea begins with the founding of Joseon (also known as "Gojoseon", or "Old Joseon", to differentiate it with the 14th century dynasty) in 2333 BCE by the legendary Dangun.[29][30] Gojoseon was noted in Chinese records in the early 7th century.[31] Gojoseon expanded until it controlled the northern Korean Peninsula and parts of Manchuria. Gija Joseon was purportedly founded in the 12th century BCE, but its existence and role have been controversial in the modern era.[30][32] In 108 BCE, the Han dynasty defeated Wiman Joseon and installed four commanderies in the northern Korean peninsula. Three of the commanderies fell or retreated westward within a few decades. As Lelang Commandery was destroyed and rebuilt around this time, the place gradually moved toward Liaodong.[clarification needed] Thus, its force was diminished and only served as a trade center until it was conquered by Goguryeo in 313.[33][34][35]

Beginning around 300 BC, the Japonic-speaking Yayoi people from the Korean Peninsula entered the Japanese islands and displaced or intermingled with the original Jōmon inhabitants.[36] The linguistic homeland of Proto-Koreans is located somewhere in southern Siberia/Manchuria, such as the Liao River area or the Amur River area. Proto-Koreans arrived in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula at around 300 BC, replacing and assimilating Japonic-speakers and likely causing the Yayoi migration.[37]

Three Kingdoms of Korea

During the Proto–Three Kingdoms period, the states of Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, and Samhan occupied the whole Korean peninsula and southern Manchuria. From them, the Three Kingdoms of Korea emerged: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla.

Goguryeo, the largest and most powerful among them, was a highly militaristic state[38] and competed with various Chinese dynasties during its 700 years of history. Goguryeo experienced a golden age under Gwanggaeto the Great and his son Jangsu,[39][40][41][42] who both subdued Baekje and Silla during their respective reigns, achieving a brief unification of the Three Kingdoms and becoming the most dominant power on the Korean Peninsula.[43][44] In addition to contesting control of the Korean Peninsula, Goguryeo had many military conflicts with various Chinese dynasties, most notably the Goguryeo–Sui War, in which Goguryeo defeated a huge force said to number over a million men.[45]

Baekje was a maritime power,[46] sometimes called the "Phoenicia of East Asia".[47] Its maritime ability was instrumental in the dissemination of Buddhism throughout East Asia and spreading continental culture to Japan.[48][49] Baekje was once a great military power on the Korean Peninsula, especially during the time of Geunchogo,[50] but was critically defeated by Gwanggaeto the Great and declined.[citation needed] Silla was the smallest and weakest of the three, but used opportunistic pacts and alliances with the more powerful Korean kingdoms, and eventually Tang China, to its advantage.[51][52]

In 676, the unification of the Three Kingdoms by Silla led to the Northern and Southern States period, in which Balhae controlled the northern parts of Goguryeo, and much of the Korean Peninsula was controlled by Later Silla. Relationships between Korea and China remained relatively peaceful during this time. Balhae was founded by a Goguryeo general and formed as a successor state to Goguryeo. During its height, Balhae controlled most of Manchuria and parts of the Russian Far East and was called the "Prosperous Country in the East".[53]

Late Silla was a wealthy country,[54] and its metropolitan capital of Gyeongju[55] grew to become the fourth largest city in the world.[56][57][58][59] It experienced a golden age of art and culture,[60][61][62][63] exemplified by monuments such as Hwangnyongsa, Seokguram, and the Emille Bell. It also carried on the maritime legacy and prowess of Baekje, and during the 8th and 9th centuries dominated the seas of East Asia and the trade between China, Korea, and Japan, most notably during the time of Jang Bogo. In addition, Silla people made overseas communities in China on the Shandong Peninsula and the mouth of the Yangtze River.[64][65][66][67] However, Silla was later weakened due to internal strife and the revival of successor states Baekje and Goguryeo, which culminated into the Later Three Kingdoms period in the late 9th century.

Buddhism flourished during this time. Many Korean Buddhists gained great fame among Chinese Buddhist circles[68] and greatly contributed to Chinese Buddhism.[69] Examples of significant Korean Buddhists from this period include Woncheuk, Wonhyo, Uisang, Musang,[70][71][72][73] and Kim Gyo-gak. Kim was a Silla prince whose influence made Mount Jiuhua one of the Four Sacred Mountains of Chinese Buddhism.[74]

Unified dynasties

In 936, the Later Three Kingdoms were united by Wang Geon, who established Goryeo as the successor state of Goguryeo.[14][15][75][76] Balhae had fallen to the Khitan Empire in 926, and a decade later the last crown prince of Balhae fled south to Goryeo, where he was warmly welcomed and included in the ruling family by Wang Geon, thus unifying the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[77] Like Silla, Goryeo was a highly cultural state, and invented the metal movable type printing press.[26] After defeating the Khitan Empire, which was the most powerful empire of its time,[78][79] in the Goryeo–Khitan War, Goryeo experienced a golden age that lasted a century, during which the Tripitaka Koreana was completed and significant developments in printing and publishing occurred. This promoted education and the dispersion of knowledge on philosophy, literature, religion, and science. By 1100, there were 12 universities that produced notable scholars.[80][81]

However, the Mongol invasions in the 13th century greatly weakened the kingdom. Goryeo was never conquered by the Mongols, but exhausted after three decades of fighting, the Korean court sent its crown prince to the Yuan capital to swear allegiance to Kublai Khan, who accepted and married one of his daughters to the Korean crown prince.[82] Henceforth, Goryeo continued to rule Korea, though as a tributary ally to the Mongols for the next 86 years. During this period, the two nations became intertwined as all subsequent Korean kings married Mongol princesses,[82] and the last empress of the Yuan dynasty was a Korean princess. In the mid-14th century, Goryeo drove out the Mongols to regain its northern territories, briefly conquered Liaoyang, and defeated invasions by the Red Turbans. However, in 1392, General Yi Seong-gye, who had been ordered to attack China, turned his army around and staged a coup.

Yi Seong-gye declared the new name of Korea as "Joseon" in reference to Gojoseon, and moved the capital to Hanseong (one of the old names of Seoul).[83] The first 200 years of the Joseon dynasty were marked by peace and saw great advancements in science[84][85] and education,[86] as well as the creation of Hangul by Sejong the Great to promote literacy among the common people.[87] The prevailing ideology of the time was Neo-Confucianism, which was epitomized by the seonbi class: nobles who passed up positions of wealth and power to lead lives of study and integrity. Between 1592 and 1598, Japan under Toyotomi Hideyoshi launched invasions of Korea, but the advance was halted by Korean forces (most notably the Joseon Navy led by Admiral Yi Sun-sin and his renowned "turtle ship") with assistance from righteous army militias formed by Korean civilians, and Ming dynasty Chinese troops.[88] Through a series of successful battles of attrition, the Japanese forces were eventually forced to withdraw, and relations between all parties became normalized. However, the Manchus took advantage of Joseon's war-weakened state and invaded in 1627 and 1637 and then went on to conquer the destabilized Ming dynasty. After normalizing relations with the new Qing dynasty, Joseon experienced a nearly 200-year period of peace. Kings Yeongjo and Jeongjo particularly led a new renaissance of the Joseon dynasty during the 18th century.[89][90]

In the 19th century, Joseon began experiencing economic difficulties and widespread uprisings, including the Donghak Peasant Revolution. The royal in-law families had gained control of the government, leading to mass corruption and weakening of the state.[citation needed] In addition, the strict isolationism of the Joseon government that earned it "the hermit kingdom" became increasing ineffective due to increasing encroachment from powers such as Japan, Russia, and the United States. This is exemplified by the Joseon–United States Treaty of 1882, in which it was compelled to open its borders.

Japanese occupation and World War II

In the late 19th century, Japan became a significant regional power after winning the First Sino-Japanese War against Qing China and the Russo-Japanese War against the Russian Empire. In 1897, King Gojong, the last king of Korea, proclaimed Joseon as the Korean Empire. However, Japan compelled Korea to become its protectorate in 1905 and formally annexed it in 1910. What followed was a period of forced assimilation, in which Korean language, culture, and history were suppressed.[91] This led to the March First Movement protests in 1919 and the subsequent foundation of resistance groups in exile, primarily in China. Among the resistance groups was Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea.[92]

Towards the end of World War II, the U.S. proposed dividing the Korean peninsula into two occupation zones: a U.S. zone and a Soviet zone. Dean Rusk and Charles H. Bonesteel III suggested the 38th parallel as the dividing line, as it placed Seoul under U.S. control. To the surprise of Rusk and Bonesteel, the Soviets accepted their proposal and agreed to divide Korea.[93]

Modern history

Despite intentions to liberate a unified peninsula in the 1943 Cairo Declaration, escalating tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States led to the division of Korea into two political entities in 1948: North Korea and South Korea.

In the South, the United States appointed and supported the former head of the Korean Provisional Government Syngman Rhee as leader. Rhee won the first presidential elections of the newly declared Republic of Korea in May 1948. In the North, the Soviets backed a former anti-Japanese guerrilla and communist activist, Kim Il Sung, who was appointed premier of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in September.[95]

In October, the Soviet Union declared Kim Il Sung's government as sovereign over both the north and south. The UN declared Rhee's government as "a lawful government having effective control and jurisdiction over that part of Korea where the UN Temporary Commission on Korea was able to observe and consult" and the government "based on elections which was observed by the Temporary Commission" in addition to a statement that "this is the only such government in Korea."[96] Both leaders engaged in authoritarian repression of political opponents.[97] South Korea requested military support from the United States but was denied,[98] and North Korea's military was heavily reinforced by the Soviet Union.[99][100]

Korean War

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea, sparking the Korean War, the Cold War's first major conflict, which continued until 1953. At the time, the Soviet Union had boycotted the UN, thus forfeiting their veto rights. This allowed the UN to intervene in a civil war when it became apparent that the superior North Korean forces would unify the entire country. The Soviet Union and China backed North Korea, with the later participation of millions of Chinese troops. After an ebb and flow that saw both sides facing defeat with massive losses among Korean civilians in both the north and the south, the war eventually reached a stalemate. During the war, Rhee's party promoted the One-People Principle, an effort to build an obedient citizenry through ethnic homogeneity and authoritarian appeals to nationalism.[101]

The 1953 armistice, never signed by South Korea, split the peninsula along the demilitarized zone near the original demarcation line. No peace treaty was ever signed, resulting in the two countries remaining technically at war. Approximately 3 million people died in the Korean War, with a higher proportional civilian death toll than World War II or the Vietnam War, making it one of the deadliest conflicts of the Cold War era.[102][103] In addition, virtually all of Korea's major cities were destroyed by the war.[104]

Post-Korean War (1960–1990)

In 1960, a student uprising (the "April Revolution") led to the resignation of the autocratic President Syngman Rhee. This was followed by 13 months of political instability as South Korea was led by a weak and ineffectual government. This instability was broken by the May 16, 1961, coup led by General Park Chung Hee. As president, Park oversaw a period of rapid export-led economic growth enforced by political repression. Under Park, South Korea took an active role in the Vietnam War.[105]

Park was heavily criticized as a ruthless military dictator, who in 1972 extended his rule by creating a new constitution, which gave the president sweeping (almost dictatorial) powers and permitted him to run for an unlimited number of six-year terms. The Korean economy developed significantly during Park's tenure. The government developed the nationwide expressway system, the Seoul subway system, and laid the foundation for economic development during his 17-year tenure, which ended with his assassination in 1979.

The years after Park's assassination were marked again by political turmoil, as the previously suppressed opposition leaders all campaigned to run for president in the sudden political void. In 1979, General Chun Doo-hwan led the coup d'état of December Twelfth. Following the coup d'état, Chun planned to rise to power through several measures. On May 17, Chun forced the Cabinet to expand martial law to the whole nation, which had previously not applied to Jeju Island. The expanded martial law closed universities, banned political activities, and further curtailed the press. Chun's assumption of the presidency through the events of May 17 triggered nationwide protests demanding democracy; these protests were particularly focused, Gwangju, to which Chun sent special forces to violently suppress the Gwangju Democratization Movement.[106]

Chun subsequently created the National Defense Emergency Policy Committee and took the presidency according to his political plan. Chun and his government held South Korea under a despotic rule until 1987, when a Seoul National University student, Park Jong-chul, was tortured to death.[107] On June 10, the Catholic Priests Association for Justice revealed the incident, igniting the June Democratic Struggle across the country. Eventually, Chun's party, the Democratic Justice Party, and its leader, Roh Tae-woo, announced the June 29 Declaration, which included the direct election of the president. Roh went on to win the election by a narrow margin against the two main opposition leaders, Kim Dae-jung and Kim Young-sam. Seoul hosted the Olympic Games in 1988, widely regarded as successful and a significant boost for South Korea's global image and economy.[108]

South Korea was formally invited to become a member of the United Nations in 1991. The transition of Korea from autocracy to modern democracy was marked in 1997 by the election of Kim Dae-jung, who was sworn in as the eighth president of South Korea on February 25, 1998. His election was significant given that he had in earlier years been a political prisoner sentenced to death (later commuted to exile). He won against the backdrop of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, where he took IMF advice to restructure the economy and the nation soon recovered its economic growth, albeit at a slower pace.[109]

Contemporary history

In June 2000, as part of President Kim Dae-jung's "Sunshine Policy" of engagement, a North–South summit took place in Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.[110] Later that year, Kim received the Nobel Peace Prize "for his work for democracy and human rights in South Korea and in East Asia in general, and for peace and reconciliation with North Korea in particular".[111] However, because of discontent among the population for fruitless approaches to the North under the previous administrations and, amid North Korean provocations, a conservative government was elected in 2007 led by President Lee Myung-bak, former mayor of Seoul.[112] Meanwhile, South Korea and Japan jointly co-hosted the 2002 FIFA World Cup.[113] However, South Korean and Japanese relations later soured because of conflicting claims of sovereignty over the Liancourt Rocks.[114]

In 2010, there was an escalation in attacks by North Korea. In March 2010 the South Korean warship ROKS Cheonan was sunk killing 46 South Korean sailors, allegedly by a North Korean submarine. In November 2010 Yeonpyeongdo was attacked by a significant North Korean artillery barrage, with 4 people dying. The lack of a strong response to these attacks from both South Korea and the international community (the official UN report declined to explicitly name North Korea as the perpetrator for the Cheonan sinking) caused significant anger with the South Korean public.[116]

South Korea saw another milestone in 2012 with the first ever female President Park Geun-hye elected and assuming office. The daughter of former President Park Chung Hee, she carried on a conservative brand of politics.[117] President Park Geun-hye's administration was formally accused of corruption, bribery, and influence-peddling for the involvement of close friend Choi Soon-sil in state affairs. There followed a series of massive public demonstrations from November 2016,[118] and she was removed from office.[119] After the fallout of Park's impeachment and dismissal, elections were held and Moon Jae-in of the Democratic Party won the presidency, assuming office on May 10, 2017.[120] His tenure saw an improving political relationship with North Korea, some increasing divergence in the military alliance with the United States, and the successful hosting of the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang.[121] In April 2018, Park Geun-hye was sentenced to 24 years in jail because of abuse of power and corruption.[122] The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the nation since 2020. That same year, South Korea recorded more deaths than births, resulting in a population decline for the first time on record.[123]

In March 2022, Yoon Suk Yeol, the candidate of conservative opposition People Power Party, won a close election over the Democratic Party candidate by the narrowest margin ever. Yoon was sworn in on May 10, 2022.[124]

Geography

South Korea occupies the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula, which extends some 1,100 km (680 mi) from the Continental and East Asian mainland. This mountainous peninsula is flanked by the Yellow Sea to the west and the Sea of Japan to the east. Its southern tip lies on the Korea Strait and the East China Sea. The country, including all its islands, lies between latitudes 33° and 39°N, and longitudes 124° and 130°E. Its total area is 100,410 square kilometers (38,768.52 sq mi).[6]

South Korea can be divided into four general regions: an eastern region of high mountain ranges and narrow coastal plains; a western region of broad coastal plains, river basins, and rolling hills; a southwestern region of mountains and valleys; and a southeastern region dominated by the broad basin of the Nakdong River.[125] South Korea is home to three terrestrial ecoregions: Central Korean deciduous forests, Manchurian mixed forests, and Southern Korea evergreen forests.[126] South Korea's terrain is mostly mountainous, most of which is not arable. Lowlands, located primarily in the west and southeast, make up only 30% of the total land area. South Korea has 20 national parks and popular nature places like the Boseong Tea Fields, Suncheon Bay Ecological Park, and Jirisan.[127]

About 3,000 islands, mostly small and uninhabited, lie off the western and southern coasts of South Korea. Jeju Province is about 100 kilometers (62 miles) off the southern coast of South Korea. It is the country's largest island, with an area of 1,845 square kilometers (712 square miles). Jeju is also the site of South Korea's highest point: Hallasan, an extinct volcano, reaches 1,950 meters (6,400 feet) above sea level. The easternmost islands of South Korea include Ulleungdo and Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo/Takeshima), while Marado and Socotra Rock are the southernmost islands of South Korea.[125]

Climate

| Seoul | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

South Korea tends to have a humid continental climate and a humid subtropical climate, and is affected by the East Asian monsoon, with precipitation heavier in summer during a short rainy season called jangma, which begins end of June and lasts through the end of July. In Seoul, the average January temperature range is −7 to 1 °C (19 to 34 °F), and the average August temperature range is 22 to 30 °C (72 to 86 °F). Winter temperatures are higher along the southern coast and considerably lower in the mountainous interior.[129] Summer can be uncomfortably hot and humid, with temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F) in most parts of the country. South Korea has four distinct seasons; spring, summer, autumn and winter. Spring usually lasts from late March to early May, summer from mid-May to early September, autumn from mid-September to early November, and winter from mid-November to mid-March.

Rainfall is concentrated in the summer months of June through September. The southern coast is subject to late summer typhoons that bring strong winds, heavy rains and sometimes floods. The average annual precipitation varies from 1,370 millimeters (54 in) in Seoul to 1,470 millimeters (58 in) in Busan.

Environment

During the first 20 years of South Korea's growth surge, little effort was made to preserve the environment.[130] Unchecked industrialization and urban development have resulted in deforestation and the ongoing destruction of wetlands such as the Songdo Tidal Flat.[131] However, there have been recent efforts to balance these problems, including a government run $84 billion five-year green growth project that aims to boost energy efficiency and green technology.[132]

The green-based economic strategy is a comprehensive overhaul of South Korea's economy, utilizing nearly two percent of the national GDP. The greening initiative includes such efforts as a nationwide bike network, solar and wind energy, lowering oil dependent vehicles, backing daylight saving time and extensive usage of environmentally friendly technologies such as LEDs in electronics and lighting.[133] The country—one of the world's most wired—plans to build a nationwide next-generation network that will be 10 times faster than broadband facilities, in order to reduce energy usage.[133]

The renewable portfolio standard program with renewable energy certificates runs from 2012 to 2022.[134] Quota systems favor large, vertically integrated generators and multinational electric utilities, if only because certificates are generally denominated in units of one megawatt-hour. They are also more difficult to design and implement than a feed-in tariff.[135] Around 350 residential micro combined heat and power units were installed in 2012.[136] In 2017, South Korea was the world's seventh largest emitter of carbon emissions and the fifth largest emitter per capita. President Moon Jae-in pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero in 2050.[137][138]

Seoul's tap water recently became safe to drink, with city officials branding it "Arisu" in a bid to convince the public.[139] Efforts have also been made with afforestation projects. Another multibillion-dollar project was the restoration of Cheonggyecheon, a stream running through downtown Seoul that had earlier been paved over by a motorway.[140] One major challenge is air quality, with acid rain, sulfur oxides, and annual yellow dust storms being particular problems.[130] It is acknowledged that many of these difficulties are a result of South Korea's proximity to China, which is a major air polluter.[130] South Korea had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.02/10, ranking it 87th globally out of 172 countries.[141]

South Korea is a member of the Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity Treaty, Kyoto Protocol (forming the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), regarding UNFCCC,[142] with Mexico and Switzerland), Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (not into force), Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands, and Whaling.[143]

Government and politics

|

|

| Yoon Suk Yeol President |

Han Duck-soo Prime Minister |

The South Korean government's structure is determined by the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. Like many democratic states,[144] South Korea has a government divided into three branches: executive, judicial, and legislative. The executive and legislative branches operate primarily at the national level, although various ministries in the executive branch also carry out local functions. The judicial branch operates at both the national and local levels. Local governments are semi-autonomous and contain executive and legislative bodies of their own. South Korea is a constitutional democracy.

The constitution has been revised several times since its first promulgation in 1948 at independence. However, it has retained many broad characteristics and with the exception of the short-lived Second Republic of Korea, the country has always had a presidential system with an independent chief executive.[145] Under its current constitution the state is sometimes referred to as the Sixth Republic of Korea. The first direct election was also held in 1948.

Although South Korea experienced a series of military dictatorships from the 1960s until the 1980s, it has since developed into a successful liberal democracy. Today, the CIA World Factbook describes South Korea's democracy as a "fully functioning modern democracy",[146] while The Economist Democracy Index classifies it as a "full democracy", ranking at 24th out of 167 countries in 2022.[147] According to the V-Dem Democracy indices South Korea is 2023 the 3rd most electoral democratic country in Asia.[148] South Korea is ranked 33rd on the Corruption Perceptions Index (6th in the Asia–Pacific region), with a score of 63 out of 100.[149]

Administrative divisions

The major administrative divisions in South Korea are eleven provinces,[f] three special self-governing provinces, six metropolitan cities (self-governing cities that are not part of any province), one special metropolitan city and one special self-governing city.

| Map | Name (city/ province) | Hangul | Hanja | Populationc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Special metropolitan city (Teukbyeol-si)a | |||||

| Seoul | 서울특별시 | 서울特別市b | 9,830,452 | |||

| Metropolitan city (Gwangyeok-si)a | ||||||

| Busan | 부산광역시 | 釜山廣域市 | 3,460,707 | |||

| Daegu | 대구광역시 | 大邱廣域市 | 2,471,136 | |||

| Incheon | 인천광역시 | 仁川廣域市 | 2,952,476 | |||

| Gwangju | 광주광역시 | 光州廣域市 | 1,460,972 | |||

| Daejeon | 대전광역시 | 大田廣域市 | 1,496,123 | |||

| Ulsan | 울산광역시 | 蔚山廣域市 | 1,161,303 | |||

| Special self-governing city (Teukbyeol-jachi-si)a | ||||||

| Sejong | 세종특별자치시 | 世宗特別自治市 | 295,041 | |||

| Province (Do)a | ||||||

| Gyeonggi | 경기도 | 京畿道 | 12,941,604 | |||

| North Chungcheong | 충청북도 | 忠淸北道 | 1,595,164 | |||

| South Chungcheong | 충청남도 | 忠淸南道 | 2,120,666 | |||

| South Jeolla | 전라남도 | 全羅南道 | 1,890,412 | |||

| North Gyeongsang | 경상북도 | 慶尙北道 | 2,682,897 | |||

| South Gyeongsang | 경상남도 | 慶尙南道 | 3,377,126 | |||

| Special self-governing province (Teukbyeol-jachi-do)a | ||||||

| Jeju | 제주특별자치도 | 濟州特別自治道 | 661,511 | |||

| Gangwon | 강원특별자치도 | 江原特別自治道 | 1,545,452 | |||

| North Jeolla | 전북특별자치도 | 全北特別自治道 | 1,847,089 | |||

| Claimed Province but not controlled (North Korea) | ||||||

| North Hamgyeong | 함경북도 | 咸鏡北道 | — | |||

| South Hamgyeong | 함경남도 | 咸鏡南道 | — | |||

| North Pyeongan | 평안북도 | 平安北道 | — | |||

| South Pyeongan | 평안남도 | 平安南道 | — | |||

| Hwanghae | 황해도 | 黃海道 | — | |||

a Revised Romanisation; b See Names of Seoul; c May As of 2018[update].;[150] d Areas that belong to the territory under the Constitution of the Republic of Korea but have not been recovered.

Foreign relations

South Koreas has been a member of the United Nations since 1991, when it became a member state at the same time as North Korea. On January 1, 2007, former South Korean Foreign Minister Ban Ki-moon served as UN Secretary-General from 2007 to 2016. South Korea has developed links with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations as both a member of ASEAN Plus three, a body of observers, and the East Asia Summit (EAS). In November 2009, South Korea joined the OECD Development Assistance Committee, marking the first time a former aid recipient country joined the group as a donor member. South Korea hosted the G-20 Summit in Seoul in November 2010, a year that saw South Korea and the European Union conclude a free trade agreement (FTA) to reduce trade barriers. South Korea went on to sign a Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Australia in 2014, and another with New Zealand in 2015. South Korea and Britain have agreed to extend a period of low or zero tariffs on bilateral trade of products with parts from the European Union in October 2023.[151]

North Korea

Both North and South Korea claim complete sovereignty over the entire peninsula and outlying islands.[152] Despite mutual animosity, reconciliation efforts have continued since the initial separation between North and South Korea. Political figures such as Kim Ku worked to reconcile the two governments even after the Korean War.[153] With longstanding animosity following the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, North Korea and South Korea signed an agreement to pursue peace.[154] On October 4, 2007, Roh Moo-Hyun and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il signed an eight-point agreement on issues of permanent peace, high-level talks, economic cooperation, renewal of train services, highway and air travel, and a joint Olympic cheering squad.[154]

Despite the Sunshine Policy and efforts at reconciliation, the progress was complicated by North Korean missile tests in 1993, 1998, 2006, 2009, and 2013. By early 2009, relationships between North and South Korea were very tense; North Korea had been reported to have deployed missiles,[155] ended its former agreements with South Korea,[156] and threatened South Korea and the United States not to interfere with a satellite launch it had planned.[157] North and South Korea are still technically at war (having never signed a peace treaty after the Korean War) and share the world's most heavily fortified border.[158]

China and Russia

Historically, Korea had close relations with the dynasties in China, and some Korean kingdoms were members of the Imperial Chinese tributary system. The Korean kingdoms also ruled over some Chinese kingdoms including the Khitan people and the Manchurians before the Qing dynasty and received tributes from them.[159] In modern times, before the formation of South Korea, Korean independence fighters worked with Chinese soldiers during the Japanese occupation. However, after World War II, the People's Republic of China embraced Maoism while South Korea sought close relations with the United States. The PRC assisted North Korea with manpower and supplies during the Korean War, and in its aftermath the diplomatic relationship between South Korea and the PRC almost completely ceased. Relations thawed gradually, and South Korea and the PRC re-established formal diplomatic relations on August 24, 1992. The two countries sought to improve bilateral relations and lifted the forty-year-old trade embargo,[160] and South Korean–Chinese relations have improved steadily since 1992.[160] The Republic of Korea broke off official relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan) upon gaining official relations with the People's Republic of China, which does not recognize Taiwan's sovereignty.[161] China has become South Korea's largest trading partner by far, sending 26% of South Korean exports in 2016 worth $124 billion, as well as an additional $32 billion worth of exports to Hong Kong.[162] South Korea is also China's fourth largest trading partner, with $93 billion of Chinese imports in 2016.[163]

Following the Korean War, the Soviet Union's relation with North Korea resulted in little contact until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Since the 1990s, there has been greater trade and cooperation between the two nations.

Japan

Korea and Japan have had difficult relations since ancient times but also significant cultural exchange, with Korea acting as the gateway between East Asia and Japan. Contemporary perceptions of Japan are still largely defined by Japan's 35-year colonization of Korea in the 20th century, which is generally regarded in South Korea as having been very negative. There were no formal diplomatic ties between South Korea and Japan directly after independence at the end of World War II in 1945. South Korea and Japan eventually signed the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1965 to establish diplomatic ties. Japan is today South Korea's third largest trading partner, with 12% ($46 billion) of exports in 2016.[162]

Longstanding issues such as Japanese war crimes against Korean civilians, the negationist re-writing of Japanese textbooks relating Japanese atrocities during World War II, the territorial disputes over the Liancourt Rocks, known in South Korea as "Dokdo" and in Japan as "Takeshima",[164] and visits by Japanese politicians to the Yasukuni Shrine, honoring Japanese people (civilians and military) killed during the war continue to trouble Korean-Japanese relations. The Liancourt Rocks were the first Korean territories to be forcibly colonized by Japan in 1905. Although it was again returned to Korea along with the rest of its territory in 1951 with the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco, Japan does not recant on its claims that the Liancourt Rocks are Japanese territory.[165] In 2009, in response to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi's visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, President Roh Moo-hyun suspended all summit talks between South Korea and Japan in 2009.[166] A summit between the nations' leaders was eventually held on February 9, 2018, during the Korean held Winter Olympics.[167] South Korea asked the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to ban the Japanese Rising Sun Flag from the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo,[168][169] and the IOC said in a statement "sports stadiums should be free of any political demonstration. When concerns arise at games time we look at them on a case-by-case basis."[170]

European Union

The European Union (EU) and South Korea are important trading partners, having negotiated a free trade agreement for many years since South Korea was designated as a priority FTA partner in 2006. The free trade agreement was approved in September 2010, and took effect on July 1, 2011.[171] South Korea is the EU's tenth largest trade partner, and the EU has become South Korea's fourth largest export destination. EU trade with South Korea exceeded €90 billion in 2015 and has enjoyed an annual average growth rate of 9.8% between 2003 and 2013.[172]

The EU has been the single largest foreign investor in South Korea since 1962, and accounted for almost 45% of all FDI inflows into Korea in 2006. Nevertheless, EU companies have significant problems accessing and operating in the South Korean market because of stringent standards and testing requirements for products and services often creating barriers to trade. Both in its regular bilateral contacts with South Korea and through its FTA with Korea, the EU is seeking to improve the current geopolitical situation.[172]

United States

A close relationship with the United States began directly after World War II, when the United States temporarily administered Korea for three years (mainly in the South, with the Soviet Union engaged in North Korea). Upon the onset of the Korean War in 1950, U.S. forces were sent to defend against an invasion from North Korea of the South and subsequently fought as the largest contributor of UN troops. The United States participation was critical for preventing the near defeat of the Republic of Korea by northern forces, as well as fighting back for the territory gains that define the South Korean nation today.

Following the Armistice, South Korea and the U.S. agreed to a "Mutual Defense Treaty", under which an attack on either party in the Pacific area would summon a response from both.[173] In 1967, South Korea obliged the mutual defense treaty by sending a large combat troop contingent to support the United States in the Vietnam War. The two nations have strong economic, diplomatic, and military ties, although they have at times disagreed with regard to policies towards North Korea and with regard to some of South Korea's industrial activities that involve usage of rocket or nuclear technology. There had also been strong anti-American sentiment during certain periods, which has largely moderated in the modern day.[174]

The two nations also share a close economic relationship, with the U.S. being South Korea's second largest trading partner, receiving $66 billion in exports in 2016.[162] In 2007, a free trade agreement known as the Republic of Korea-United States Free Trade Agreement was signed between South Korea and the United States, but its formal implementation was repeatedly delayed, pending approval by the legislative bodies of the two countries. On October 12, 2011, the U.S. Congress passed the long-stalled trade agreement with South Korea.[175] It went into effect on March 15, 2012.[176]

Military

Unresolved tension with North Korea has prompted South Korea to allocate 2.6% of its GDP and 13.2% of all government spending to its military (government share of GDP: 14.967%), while maintaining compulsory conscription for men.[177] Consequently, the ROK Armed Forces is one of the largest and most powerful standing armed forces in the world with a reported personnel strength of 3,600,000 in 2022 (500,000 active and 3,100,000 reserve).[178]

The South Korean military consists of the Army (ROKA), the Navy (ROKN), the Air Force (ROKAF), and the Marine Corps (ROKMC), and reserve forces. Many of these forces are concentrated near the Korean Demilitarized Zone. All South Korean males are constitutionally required to serve in the military, typically 18 months.[179] In addition Korean Augmentation to the United States Army is a branch of the Republic of Korea Army that consists of Korean enlisted personnel who are augmented to the Eighth United States Army. In 2010, South Korea spent ₩1.68 trillion in a cost-sharing agreement with the U.S. to provide budgetary support to the U.S. forces in Korea, on top of the ₩29.6 trillion budget for its own military.

From time to time, South Korea has sent its troops overseas to assist American forces. It has participated in most major conflicts that the United States has been involved in the past 50 years. South Korea dispatched 325,517 troops to fight in the Vietnam War, with a peak strength of 50,000.[180] In 2004, South Korea sent 3,300 troops of the Zaytun Division to help rebuilding in northern Iraq, and was the third largest contributor in the coalition forces after the U.S. and Britain.[181] Beginning in 2001, South Korea had deployed 24,000 troops in the Middle East region to support the war on terror.

The right to conscientious objection was not recognized in South Korea until recently. Over 400 men were typically imprisoned at any given time for refusing military service for political or religious reasons in the years before right to conscientious objection was established.[182] On June 28, 2018, the South Korean Constitutional Court ruled the Military Service Act unconstitutional and ordered the government to accommodate civilian forms of military service for conscientious objectors.[183] On November 1, 2018, the South Korean Supreme Court legalized conscientious objection as a basis for rejecting compulsory military service.[184]

United States contingent

The United States has stationed a substantial contingent of troops to defend South Korea. There are approximately 28,500 U.S. military personnel stationed in South Korea,[185] most of them serving one year unaccompanied tours. The U.S. troops, which are primarily ground and air units, are assigned to United States Forces Korea and mainly assigned to the Eighth Army, Seventh Air Force, and Naval Forces Korea. They are stationed in installations at Osan, Kunsan, Yongsan, Dongducheon, Sungbuk, Camp Humphreys, and Daegu, as well as at Camp Bonifas in the DMZ Joint Security Area.

A fully functioning UN Command is at the top of the chain of command of all forces in South Korea, including the U.S. forces and the entire South Korean military – if a sudden escalation of war between North and South Korea were to occur the United States would assume control of the South Korean armed forces in all military and paramilitary moves. There has been long-term agreement between the United States and South Korea that South Korea should eventually assume the lead for its own defense. This transition to a South Korean command has been slow and often postponed, although it is currently scheduled to occur in the 2020s.[186]

Economy

South Korea's mixed economy[187][188][189] is the 13th largest GDP at nominal and the 14th largest GDP by purchasing power parity in the world,[190] identifying it as one of the G20 major economies. It is a developed country with a high-income economy and is the most industrialized member country of the OECD. South Korean brands such as LG Electronics and Samsung are internationally famous and garnered South Korea's reputation for its quality electronics and other manufactured goods.[191] South Korea became a member of the OECD in 1996.[192]

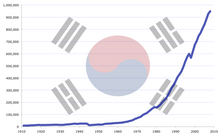

Its massive investment in education has taken the country from mass illiteracy to a major international technological powerhouse. The country's national economy benefits from a highly skilled workforce and is among the most educated countries in the world with one of the highest percentages of its citizens holding a tertiary education degree.[193] South Korea's economy was one of the world's fastest-growing from the early 1960s to the late 1990s, and was still one of the fastest-growing developed countries in the 2000s, along with Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan, the other three Asian Tigers.[194] It recorded the fastest rise in average GDP per capita in the world between 1980 and 1990.[195] South Koreans refer to this growth as the Miracle on the Han River.[196] The South Korean economy is heavily dependent on international trade, and in 2014, South Korea was the fifth-largest exporter and seventh-largest importer in the world. In addition, the country has one of the world's largest foreign-exchange reserves.[197]

Despite the economy's high growth potential and apparent structural stability, the country suffers damage to its credit rating in the stock market because of the belligerence of North Korea in times of deep military crises, which has an adverse effect on its financial markets.[198][199] The International Monetary Fund compliments the resilience of the economy against various economic crises, citing low state debt and high fiscal reserves that can quickly be mobilized to address financial emergencies.[200] Although it was severely harmed by the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the country managed a rapid recovery and subsequently tripled its GDP.[201]

Furthermore, South Korea was one of the few developed countries that was able to avoid a recession during the global financial crisis of 2007–08.[202] Its economic growth rate reached 6.2% in 2010 (the fastest growth for eight years after significant growth by 7.2% in 2002),[203] a sharp recovery from economic growth rates of 2.3% in 2008 and 0.2% in 2009 during the Great Recession. The unemployment rate also remained low in 2009 at 3.6%.[204]

Transportation

South Korea has a technologically advanced transport network consisting of high-speed railways, highways, bus routes, ferry services, and air routes that crisscross the country. Korea Expressway Corporation operates the toll highways and service amenities en route. Korail provides train services to all major South Korean cities. Two rail lines, Gyeongui and Donghae Bukbu Line, to North Korea are being reconnected. The Korean high-speed rail system, KTX, provides high-speed service along Gyeongbu and Honam Line. Major cities have urban rapid transit systems.[205] Express bus terminals are available in most cities.[206]

The main gateway and largest airport is Incheon International Airport, serving 58 million passengers in 2016.[207] Other international airports include Gimpo, Busan and Jeju. There are also many airports that were built as part of the infrastructure boom but are barely used.[208] There are also many heliports.[209] The national carrier Korean Air served over 26 million passengers, including almost 19 million international passengers in 2016.[210] A second carrier, Asiana Airlines also serves domestic and international traffic. Combined, South Korean airlines serve 297 international routes.[211] Smaller airlines, such as Jeju Air, provide domestic service with lower fares.[212]

Energy

South Korea is the world's fifth-largest nuclear power producer and the third-largest in Asia as of 2010[update].[213] Supplying 45% of its electricity production, nuclear research is very active with investigation into a variety of advanced reactors, including a small modular reactor, a liquid-metal fast/transmutation reactor and a high-temperature hydrogen generation design. Fuel production and waste handling technologies have also been developed locally. It is also a member of the ITER project.[214]

South Korea is an emerging exporter of nuclear reactors, having concluded agreements with the United Arab Emirates to build and maintain four advanced nuclear reactors,[215] with Jordan for a research nuclear reactor,[216][217] and with Argentina for construction and repair of heavy-water nuclear reactors.[218][219] As of 2010[update], South Korea and Turkey are in negotiations regarding construction of two nuclear reactors.[220] South Korea is also preparing to bid on construction of a light-water nuclear reactor for Argentina.[219]

South Korea is not allowed to enrich uranium or develop traditional uranium enrichment technology on its own, because of U.S. political pressure,[221] unlike most major nuclear powers such as Japan, Germany, and France, competitors in the international nuclear market. This impediment to South Korea's indigenous nuclear industrial undertaking has sparked occasional diplomatic rows between the two allies. While successful in exporting its electricity-generating nuclear technology and nuclear reactors, it cannot capitalize on the market for nuclear enrichment facilities and refineries, preventing it from further expanding its export niche. South Korea has sought unique technologies such as pyroprocessing to circumvent these obstacles and seek a more advantageous competition.[222] The U.S. has recently been wary of the burgeoning nuclear program, which South Korea insists will be for civilian use only.[213]

South Korea is the 2nd highest ranked Continental Asian country in the World Economic Forum's Networked Readiness Index after Singapore—an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. South Korea ranks 9th worldwide.[223]

Tourism

In 2019, more than 17 million foreign tourists visited South Korea.[224] South Korean tourism is driven by many factors, including the prominence of Korean pop culture such as South Korean pop music and television dramas, known as the Korean Wave or Hallyu, has gained popularity throughout East Asia. The Hyundai Research Institute reported that the Korean Wave has a direct influence on encouraging direct foreign investment back into the country through demand for products, and the tourism industry.[225] Among East Asian countries, China was the most receptive, investing $1.4 billion in South Korea, with much of the investment within its service sector, a sevenfold increase from 2001.

According to an analysis by economist Han Sang-Wan, a 1% increase in the exports of Korean cultural content pushes consumer goods exports up 0.083%, while a 1% increase in Korean pop content exports to a country produces a 0.019% bump in tourism.[225]

National pension scheme

The South Korean pension system was created to provide benefits to persons reaching old age, families and persons stricken with death of their primary breadwinner, and for the purposes of stabilizing the nation's welfare state.[226] The structure is primarily based on taxation and is income-related.[227] The system is divided into four categories distributing benefits to participants through national, military personnel, governmental, and private school teacher pension schemes.[228] The national pension scheme is the primary welfare system providing allowances to the majority of persons. Eligibility for the national pension scheme is not dependent on income but on age and residence, where those between the ages of 18 and 59 are covered.[229] Anyone under 18 is a dependent of someone who is covered or under a special exclusion where they are allowed to alternative provisions.[230] The national pension scheme is divided into four categories of insured persons – the workplace-based insured, the individually insured, the voluntarily insured, and the voluntarily and continuously insured. An old-age pension scheme covers individuals age 60 or older for the rest of their life as long as they have satisfied the minimum of 20 years of national pension coverage beforehand.[230]

Science and technology

Scientific and technological development in South Korea at first did not occur largely because of more pressing matters such as the division of Korea and the Korean War that occurred right after its independence. It was not until the 1960s under the dictatorship of Park Chung Hee when South Korea's economy rapidly grew from industrialization and the chaebol corporations such as Samsung, LG, and SK. Ever since the industrialization of South Korea's economy, South Korea has placed its focus on technology-based corporations, which has been supported by infrastructure developments by the government.

South Korea leads the OECD in graduates in science and engineering.[231] From 2014 to 2019, the country ranked first among the most innovative countries in the Bloomberg Innovation Index.[232] It was ranked 6th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[233] Republic of Korea South Korea today is known as a launchpad of a mature mobile market that allows developers to reap benefits of a market where very few technology constraints exist. There is a growing trend of inventions of new types of media or apps, utilizing the 4G and 5G internet infrastructure in South Korea. South Korea has the infrastructures to meet a high density of population and culture; this, along with high revenues, allows South Korean-only tech startups to reach valuations of $1 billion and above, a peak usually reserved for startups growing in several countries.[234]

Total spending for research and development grew from about 3.9% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013 to more than 4.9% in 2022 and was thus the second-highest in the world, only behind Israel which spent 5.9%. In 2023 the government announced a spending cut by about 11% for 2024 and the intention to shift resources to new initiatives, such as efforts to build rockets, pursue biomedical research, and develop US-style biotech innovation.[235]

Cyber security

Following cyberattacks in the first half of 2013, whereby government, news-media, television station, and bank websites were compromised, the national government committed to the training of 5,000 new cybersecurity experts by 2017. The South Korean government blamed North Korea for these attacks, as well as incidents that occurred in 2009, 2011 and 2012, but Pyongyang denies the accusations.[236] South Korea's government maintains a broad-ranging approach toward the regulation of specific online content and imposes a substantial level of censorship on election-related discourse and on many websites that the government deems subversive or socially harmful.[237][238]

Aerospace engineering

South Korea has sent up 10 satellites since 1992, all using foreign rockets and overseas launch pads, notably Arirang-1 in 1999, and Arirang-2 in 2006 as part of its space partnership with Russia.[239] Arirang-1 was lost in space in 2008, after nine years in service.[240] In April 2008, Yi So-yeon became the first Korean to fly in space, aboard the Russian Soyuz TMA-12.[241][242]

In June 2009, the first spaceport of South Korea, Naro Space Center, was completed at Goheung, South Jeolla Province.[243] The launch of Naro-1 in January 2013 was a success, after two previous failed attempts.[244]

Efforts to build an indigenous space launch vehicle have been marred by persistent political pressure from the United States, who had for many decades hindered South Korea's indigenous rocket and missile development programs[245] in fear of their possible connection to clandestine military ballistic missile programs, which Korea many times insisted did not violate the research and development guidelines stipulated by US-Korea agreements on restriction of rocket technology research and development.[246] South Korea has sought the assistance of foreign countries such as Russia through MTCR commitments to supplement its restricted domestic rocket technology. The two failed KSLV-I launch vehicles were based on the Universal Rocket Module, the first stage of the Russian Angara rocket, combined with a solid-fueled second stage built by South Korea.

On October 21, 2021, the KSLV-2 Nuri was successfully launched, and South Korea became a country with its own space projectile technology.[247]

Robotics

Robotics has been included in the list of main national research and development projects since 2003.[248] In 2009, the government announced plans to build robot-themed parks in Incheon and Masan with a mix of public and private funding.[249] In 2005, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) developed the world's second walking humanoid robot, HUBO. A team in the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology developed the first Korean android, EveR-1 in May 2006.[250] EveR-1 has been succeeded by more complex models with improved movement and vision.[251][252]

Plans of creating English-teaching robot assistants to compensate for the shortage of teachers were announced in February 2010, with the robots being deployed to most preschools and kindergartens by 2013.[253] Robotics are also incorporated in the entertainment sector; the Korean Robot Game Festival has been held every year since 2004 to promote science and robot technology.[254]

Biotechnology

Since the 1980s, the government has invested in the development of a domestic biotechnology industry.[255] The medical sector accounts for a large part of the production, including production of hepatitis vaccines and antibiotics. Research and development in genetics and cloning has received increasing attention, with the first successful cloning of a dog, Snuppy in 2005, and the cloning of two females of an endangered species of gray wolves by the Seoul National University in 2007.[256] The rapid growth of the industry has resulted in significant voids in regulation of ethics, as was highlighted by the scientific misconduct case involving Hwang Woo-Suk.[257]

Since late 2020, SK Bioscience Inc. (a division of SK Group) has been producing a major proportion of the Vaxzevria vaccine (also known as COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca), under license from the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca, for worldwide distribution through the COVAX facility under the WHO hospice. A recent agreement with Novavax expands its production for a second vaccine to 40 million doses in 2022, with a $450 million investment in domestic and overseas facilities.[258]

Demographics

South Korea had an estimated population of roughly 51.7 million in 2022.[259][260] Despite its population more than doubling since 1960,[261] South Korea's birth rate became the world's lowest in 2009,[262] at an annual rate of approximately 9 births per 1000 people.[263] Fertility saw some modest increase afterwards,[264] but dropped to a new global low in 2017,[265] with fewer than 30,000 births per month for the first time since records began,[266] and less than 1 child per woman in 2018.[267] Consequently, in 2020, the country recorded more deaths than births, resulting in the first population decrease since modern records began.[268][269] By 2021, the fertility rate stood at just 0.81 children per woman,[270] well below the replacement rate of 2.1, and fell further to 0.78 in 2022 and 0.72 in 2023—the lowest in the world. Consequently, South Korea has the steepest decline in working age population among OECD nations,[271] with the proportion of people aged 65 years and over slated to reach over 20% by 2025 and close to 45% by 2050.[272]

South Korea is noted for its population density, which was an estimated 514.6 per square kilometre (1,333/sq mi) in 2022,[259] more than 10 times the global average.

Most South Koreans live in urban areas following rapid migration from the countryside during the country's rapid economic expansion in the 1970s through the 1990s.[273] About half the population (24.5 million) is concentrated in the Seoul National Capital Area, making it the world's second largest metropolitan area; other major cities include Busan (3.5 million), Incheon (3.0 million), Daegu (2.5 million), Daejeon (1.4 million), Gwangju (1.4 million) and Ulsan (1.1 million).[274]

The population has been shaped by international migration. After World War II and the division of the Korean Peninsula, about four million people from North Korea crossed the border to South Korea. This trend of net entry reversed over the next 40 years because of emigration, especially to North America through the United States and Canada. South Korea's total population in 1955 was 21.5 million,[275] which would more than double to 50 million by 2010.[261]

South Korea is considered one of the most ethnically homogeneous societies in the world, with ethnic Koreans representing approximately 96% of total population. Precise numbers are difficult to estimate since statistics do not record ethnicity, given that many immigrants are ethnically Korean themselves, and some South Korean citizens are not ethnically Korean.[276]

The percentage of foreign nationals has been growing rapidly since late 1990s.[277] As of 2016[update], South Korea had 1,413,758 foreign residents, 2.75% of the population;[276] however, many of them are ethnic Koreans with a foreign citizenship. For example, migrants from China (PRC) make up 56.5% of foreign nationals, but approximately 70% of the Chinese citizens in Korea are Joseonjok (조선족), PRC citizens of Korean ethnicity.[278] In addition, about 43,000 English teachers from English-speaking countries reside temporarily in Korea.[279] South Korea has one of the highest rates of growth of foreign born population, with about 30,000 foreign born residents obtaining South Korean citizenship every year since 2010.

Large numbers of ethnic Koreans live overseas, sometimes in Korean ethnic neighborhoods also known as Koreatowns. The four largest diaspora populations can be found in China (2.3 million), the United States (1.8 million), Japan (0.85 million), and Canada (0.25 million).

Corresponding to its socioeconomic development, South Korea has experienced a dramatic increase in life expectancy, from 79.10 years in 2008[280] (which was 34th in the world),[281] to 83.53 years in 2024—the fifth highest of any country or territory.

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seoul  Busan |

1 | Seoul | Seoul | 9,904,312 | 11 | Yongin | Gyeonggi | 971,327 |  Incheon  Daegu |

| 2 | Busan | Busan | 3,448,737 | 12 | Seongnam | Gyeonggi | 948,757 | ||

| 3 | Incheon | Incheon | 2,890,451 | 13 | Bucheon | Gyeonggi | 843,794 | ||

| 4 | Daegu | Daegu | 2,446,052 | 14 | Cheongju | North Chungcheong | 833,276 | ||

| 5 | Daejeon | Daejeon | 1,538,394 | 15 | Ansan | Gyeonggi | 747,035 | ||

| 6 | Gwangju | Gwangju | 1,502,881 | 16 | Jeonju | North Jeolla | 658,172 | ||

| 7 | Suwon | Gyeonggi | 1,194,313 | 17 | Cheonan | South Chungcheong | 629,062 | ||

| 8 | Ulsan | Ulsan | 1,166,615 | 18 | Namyangju | Gyeonggi | 629,061 | ||

| 9 | Changwon | South Gyeongsang | 1,059,241 | 19 | Hwaseong | Gyeonggi | 608,725 | ||

| 10 | Goyang | Gyeonggi | 990,073 | 20 | Anyang | Gyeonggi | 585,177 | ||

Language

Korean is the official language of South Korea and is classified by most linguists as a language isolate. It incorporates a significant number of loan words from Chinese. Korean uses an indigenous writing system called Hangul, created in 1446 by King Sejong, to provide a convenient alternative to the Classical Chinese Hanja characters that were difficult to learn and did not fit the Korean language well. South Korea still uses some Chinese Hanja characters in limited areas, such as print media and legal documentation.

The Korean language in South Korea has a standard dialect known as the Seoul dialect, with an additional four dialects (Chungcheong, Gangwon, Gyeongsang, and Jeolla) and one language (Jeju) in use around the country. Almost all South Korean students today learn English throughout their education.[283][284]

Religion

Religion in South Korea (2015 census)[285][4]

According to the results of the census of 2015, more than half of the South Korean population (56.1%) declared themselves not affiliated with any religious organizations.[285] In a 2012 survey, 52% declared themselves "religious", 31% said they were "not religious" and 15% identified themselves as "convinced atheists".[286] Of the people who are affiliated with a religious organization, most are Christians and Buddhists. According to the 2015 census, 27.6% of the population were Christians (19.7% identified themselves as Protestants, 7.9% as Roman Catholics) and 15.5% were Buddhists.[285] Other religions include Islam (130,000 Muslims, mostly migrant workers from Pakistan and Bangladesh but including some 35,000 Korean Muslims[287]), the homegrown sect of Won Buddhism, and a variety of indigenous religions, including Cheondoism (a Confucianizing religion), Jeungsanism, Daejongism, Daesun Jinrihoe, and others. Freedom of religion is guaranteed by the constitution, and there is no state religion.[288] Overall, between the 2005 and 2015 censuses, there has been a slight decline of Christianity (down from 29% to 27.6%), a sharp decline of Buddhism (down from 22.8% to 15.5%), and a rise of the unaffiliated population (from 47.2% to 56.9%).[285]

Christianity is South Korea's largest organized religion, accounting for more than half of all South Korean adherents of religious organizations. There are approximately 13.5 million Christians in South Korea today; about two thirds of them belonging to Protestant churches, and the rest to the Catholic Church.[285] The number of Protestants had been stagnant throughout the 1990s and the 2000s but increased to a peak level throughout the 2010s. Roman Catholics increased significantly between the 1980s and the 2000s but declined throughout the 2010s.[285] Christianity, unlike in other East Asian countries, found fertile ground in Korea in the 18th century, and by the end of the 18th century it persuaded a large part of the population, as the declining monarchy supported it and opened the country to widespread proselytism as part of a project of Westernization. The weakness of Korean Sindo, which—unlike Japanese Shinto and China's religious system—never developed into a national religion of high status,[289] combined with the impoverished state of Korean Buddhism, (after 500 years of suppression at the hands of the Joseon state, by the 20th century it was virtually extinct) left a free hand to Christian churches. Christianity's similarity to native religious narratives has been studied as another factor that contributed to its success in the peninsula.[290] The Japanese colonization of the first half of the 20th century further strengthened the identification of Christianity with Korean nationalism, as the Japanese coopted native Korean Sindo into the Nipponic Imperial Shinto that they tried to establish in the peninsula.[291] Widespread Christianization of the Koreans took place during State Shinto,[291] after its abolition, and then in the independent South Korea as the newly established military government supported Christianity and tried to utterly oust native Sindo.

Among Christian denominations, Presbyterianism is the largest. About nine million people belong to one of the hundred different Presbyterian churches; the biggest ones are the HapDong Presbyterian Church, TongHap Presbyterian Church and the Koshin Presbyterian Church. South Korea is also the second-largest missionary-sending nation, after the United States.[292]

Buddhism was introduced to Korea in the 4th century.[293] It soon became a dominant religion in the southeastern kingdom of Silla, the region that hitherto hosts the strongest concentration of Buddhists in South Korea. In the other states of the Three Kingdoms Period, Goguryeo and Baekje, it was made the state religion respectively in 372 and 528. It remained the state religion in Later Silla and Goryeo. It was later suppressed throughout much of the subsequent history under the unified kingdom of Joseon, which officially adopted a strict Korean Confucianism. Today, South Korea has about 7 million Buddhists,[285] most of them affiliated to the Jogye Order. Most of the National Treasures of South Korea are Buddhist artifacts.

Education

A centralized administration in South Korea oversees the process for the education of children from kindergarten to the third and final year of high school. The school year is divided into two semesters, the first of which begins at the beginning of March and ends in mid-July, the second of which begins in late August and ends in mid-February. The country adopted a new educational program to increase the number of their foreign students through 2010. According to the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, the number of scholarships for foreign students in South Korea would have (under the program) doubled by that time, and the number of foreign students would have reached 100,000.[294]

South Korea is one of the top-performing Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in reading literacy, mathematics and sciences with the average student scoring 519, compared with the OECD average of 492, placing it ninth in the world. The country has one of the world's highest-educated labor forces among OECD countries.[295][296] The country is well known for its highly feverish outlook on education, where its national obsession with education has been called "education fever".[297][298][299] This obsession with education has catapulted the resource-poor nation consistently atop the global education rankings. In 2014, South Korea ranked second worldwide (after Singapore) in the national rankings of students' math and science scores by the OECD.[300] Higher education is a serious issue in South Korean society, where it is viewed as one of the fundamental cornerstones of South Korean life. Education is regarded with a high priority for South Korean families, as success in education is often a source of honor and pride for families and within South Korean society at large, and is seen as a fundamental necessity to channel one's social mobility to ultimately improve one's socioeconomic position in South Korean society.[301][302]

In 2015, the country spent 5.1% of its GDP on all levels of education—roughly 0.8 percentage points above the OECD average of 4.3%.[303] A strong investment in education, a militant drive to achieve academic success, as well as the passion for scholarly excellence has helped the resource-poor country rapidly grow its economy over the past 60 years from a war-torn land to a prosperous, developed country.[304]

Health

South Korea has a universal health care system.[305] According to the Health Care Index ranking, it has the world's best healthcare system as of 2021.[306] South Korean hospitals have advanced medical equipment and facilities readily available, ranking 4th for MRI units per capita and 6th for CT scanners per capita in the OECD.[307] It also had the OECD's second largest number of hospital beds per 1000 people at 9.56 beds. Life expectancy has been rising rapidly and South Korea ranked 6th in the world for life expectancy at 83.5 years in 2023.[308] It also has the third highest health adjusted life expectancy in the world.[309] Suicide in South Korea is the 12th highest in the world according to the World Health Organization, as well as the highest suicide rate in the OECD.[310][311]

Culture