Troy H. Middleton

Troy Houston Middleton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 October 1889 Copiah County, Mississippi, United States |

| Died | 9 October 1976 (aged 86) Baton Rouge, Louisiana, United States |

| Buried | Baton Rouge National Cemetery, Louisiana, United States |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1910–1937 1942–1945 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Service number | 0-3476 |

| Unit | Infantry Branch |

| Commands | 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 47th Infantry Regiment 142nd Infantry Regiment 45th Infantry Division VIII Corps |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Silver Star Legion of Merit (2) |

| Other work | Dean of Administration, LSU Acting Vice President, LSU Comptroller, LSU President, LSU |

Lieutenant General Troy Houston Middleton (12 October 1889 – 9 October 1976) was a distinguished educator and senior officer of the United States Army who served as a corps commander in the European Theatre during World War II and later as president of Louisiana State University (LSU).

Enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1910, Middleton was first assigned to the 29th Infantry Regiment, where he worked as a clerk. Here he did not become an infantryman as he had hoped, but he was pressed into service playing football, a sport strongly endorsed by the army. Following two years of enlisted service, Middleton was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was given the opportunity to compete for an officer's commission. Of the 300 individuals who were vying for a commission, 56 were selected, and four of them, including Middleton, would become general officers. As a new second lieutenant, Middleton was assigned to the 7th Infantry Regiment in Galveston, Texas, which was soon pressed into service, responding to events created by the Mexican Revolution. Middleton spent seven months doing occupation duty in the Mexican port city of Veracruz, and later was assigned to Douglas, Arizona, where his unit skirmished with some of Pancho Villa's fighters.

Upon the entry of the United States into World War I, in April 1917, Middleton was assigned to the 4th Infantry Division, and soon saw action as a battalion commander during the Second Battle of the Marne. Three months later, following some minor support roles, his unit led the attack during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and Middleton became a regimental commander. Because of his exceptional battlefield performance, on 14 October 1918 he was promoted to the rank of colonel, becoming, at the age of 29, the youngest officer of that rank in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). He also received the Army Distinguished Service Medal for his exemplary service. Following World War I, Middleton served at the U.S. Army School of Infantry, the U.S. Army Command and General Staff School, the U.S. Army War College, and as commandant of cadets at LSU. He retired from the army in 1937 to become dean of administration and later comptroller and acting vice president at LSU. His tenure at LSU was fraught with difficulty, as Middleton became one of the key players in helping the university recover from a major scandal where nearly a million dollars had been embezzled.

Recalled to service in early 1942, upon American entry into World War II, Middleton became CG of the 45th Infantry Division during the Sicily and Salerno battles in Italy, and then in March 1944 moved up to command the VIII Corps. His leadership in Operation Cobra during the Battle of Normandy led to the capture of the important port city of Brest, France, and for his success he was awarded a second Distinguished Service Medal by General George Patton. His greatest World War II achievement, however, was in his decision to hold the important city of Bastogne, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge. Following this battle, and his corps' relentless push across Germany until reaching Czechoslovakia, he was recognized by both General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, and Patton as being a corps commander of extraordinary abilities. Middleton logged 480 days in combat during World War II, more than any other American general officer. Retiring from the army again in 1945, Middleton returned to LSU and in 1951 was appointed to the university presidency, a position he held for 11 years, while continuing to serve the army in numerous consultative capacities. He resided in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, until his death in 1976 and was buried in Baton Rouge National Cemetery. The library at Louisiana State University had been named for him, but in 2020, the LSU Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to remove his name due to his segregationist policies.[1]

Family and early life

[edit]Ancestry

[edit]Troy H. Middleton was born near Georgetown, Mississippi, on 12 October 1889, the son of John Houston Middleton and Laura Catherine "Kate" Thompson.[A][2] His paternal grandfather, Benjamin Parks Middleton, served as a private in the Mississippi Infantry for the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, and his maternal grandfather, Riden M. Thompson, was also a Confederate soldier.[3] His great-great-grandfather, Captain Holland Middleton, served from Georgia in the American Revolutionary War.[4][5] Holland Middleton was the son of William Middleton and grandson of Robert Middleton, who had extensive land interests in Charles County and Prince George's County in Maryland.[6] In 1678 Robert Middleton was paid for expenses incurred in fighting the Nanticoke Indians and in 1681 he was commissioned as cornet (second lieutenant) in a troop of cavalry.[6]

Early life

[edit]Troy Middleton was the fifth of nine children and grew up on a 400-acre plantation in southeastern Copiah County.[7] The plantation was virtually a self-contained community, and he had a variety of chores to do depending on the season, with sausage-stuffing being one of his favorites. The local Lick Creek and Strong River had plentiful fish that he would catch, and he loved to hunt, particularly with his 12-gauge shotgun.[8] While his family was Episcopal by heritage, they worshiped at the Bethel Baptist Church, a few miles west of Georgetown, the only church reachable on a Sunday morning.[9] His education was conducted at the small Bethel schoolhouse, but in the summertime he was tutored by his oldest sister Emily, who came home from Blue Mountain College to share her knowledge with her family.[10] Having exhausted all the educational opportunities available at home, Middleton's father asked him if he was interested in a college education. Finding this an attractive proposition, in the summer of 1904, at the age of fourteen, Middleton made the 172-mile train trip to Starkville, where he would begin his studies at Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College (Mississippi A&M, later Mississippi State University).[11]

College at Mississippi A&M

[edit]

At his young age, Middleton was required to complete a year of preparatory school before being enrolled in the four-year program at Mississippi A&M. In essence he did a final year of high school while living in the dormitory and following the regimen of the students at the college.[12] The students were treated like cadets at a military academy, marching to and from all meals, and beginning their day with the first bugle call at 5:30 a.m. While Middleton did not particularly savor the military atmosphere, he settled into the routine, and the year passed quickly.[13] The highlight of his preparatory year came on 10 February 1905 when John Philip Sousa brought his band to A&M, attracting people from around the state, and packing the 2000-seat mess hall. The train that would take the band to its next stop was held up for over an hour as the concert was extended by repeated calls for encores.[14]

The student corps at A&M was organized into a battalion, with a size of about 350 cadets during Middleton's first year. He began as a cadet corporal, and by his junior year was appointed as the cadet sergeant major. As a senior he had the cadet rank of lieutenant colonel and was the student commander of more than 700 cadets, in two battalions. Working with the military officer in charge of the cadets, Middleton took on additional responsibilities for which he was paid $25 per month.[15]

Middleton was involved in numerous activities during his college days, and took leadership roles in most of them. He was the vice president of A&M's Collegian Club, and president of the school's Gun Club, being photographed on one occasion with his beloved shotgun, which he was allowed to keep in his dormitory room and use for hunting on weekends.[16] He was the president of his junior class and during his senior year was the commandant of the select Mississippi Sabre Company, which was restricted to seniors of good social, academic and military standing. Among his favorite activities were baseball and football, and he played both sports throughout college, although he had to give up a season of baseball when he failed a chemistry course. Whether playing or spectating, the baseball and football games gave the students a chance to leave campus, and they took the train to play teams around the state.[17]

Middleton graduated with a bachelor's degree in the spring of 1909, and was hoping to get an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. No such opportunity presented itself, however, and at the age of 19 he was too young to take the examination for an army commission. Taking the advice of an army officer at A&M, he decided to enlist in the United States Army.[18]

Early service in the U.S. Army

[edit]Enlisted service

[edit]On 3 March 1910 Troy Middleton enlisted into the 29th Infantry Regiment at Fort Porter in Buffalo, New York.[18] He was put to work as a company clerk, and as a private earned $15 a month, which was paid in gold until it became scarce, and was then paid in silver.[19] Middleton tired of this desk work quickly and asked to become a soldier. While this did not happen at Fort Porter, his talents as a football player became known, and he was pressed into duty as the quarterback of the local team, which played civilian teams in the Buffalo area as well as other army teams.[20] For the next several years Middleton would play a lot of football, a sport that was strongly endorsed by the army. After getting a commission, an officer is never returned to the same unit from which he served as an enlisted member, but Middleton became the exception because of his talents as a quarterback. Middleton felt that football provided him with the finest training he received while in the army, and he said he never met a good football player who was not also a good soldier.[21]

Officer's commission

[edit]

After 27 months of service, Middleton got his first promotion, to corporal.[22] Promotions came very slowly, and occurred only when a position was vacated by someone else getting promoted or retiring. Shortly after his promotion on 10 June 1912, Corporal Middleton was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he would have a chance to compete for an army commission. Here Middleton attended an intensive training course to prepare for the written examination required for a second lieutenant's commission.[22] Of the 300 civilians and enlisted men who took the exam, 56 of them passed and were commissioned. Middleton's score was just about in the middle of the passing scores. Almost all of those passing were college graduates, coming from schools such as Harvard, Yale, Virginia Military Institute, and Stanford. Four of the 56, including Middleton, would go on to become general officers.[22]

In addition to taking the written exam, all of the applicants had to take a horse-riding test as well. Having grown up riding horses on his family's plantation, Middleton scored very well on this exam, and the officer in charge thought that he would want to go into the cavalry. Middleton, however, wanted to go into the infantry, leaving the officer stunned that anyone with such horsemanship skills would even consider spending his time walking.[23]

Having passed his exam, Middleton was recommended for a commission by President Howard Taft in November 1912, but it was not until after the new president, Woodrow Wilson, was sworn in the following March, and the new congress convened, that the 56 successful candidates were confirmed by the Senate. Their appointment was back-dated to 30 November 1912. During this interim period, Middleton was transferred to Fort Crockett in Galveston, Texas, where he arrived early in 1913.[24]

Fort Crockett and deployment to Mexico

[edit]In February 1913 Troy Middleton reported to Fort Crockett as a second lieutenant without a commission, being assigned to Company K of the 7th Infantry Regiment. A large part of the United States Army was rotating here in response to trouble in Mexico.[25] In 1910 Mexico's President Porfirio Diaz was overthrown by a reform leader, Francisco Madero, beginning the Mexican Revolution which would last for nearly a decade. Madero was supported by General Victoriano Huerta in putting down a series of revolts in 1912, but the following year was assassinated by the General, who then seized power. Though many countries recognized the Huerta government, President Woodrow Wilson would not, and he hoped to return Mexico to a constitutional government by backing Venustiano Carranza. The troops at Fort Crockett went into a waiting mode, preparing for the call from the President to take action in support of American interests.[25]

In April 1914 the waiting for the military units ended, and American troops under the command of Brigadier General Frederick Funston were sent into Mexico. The Navy had taken the port city of Veracruz and the 7th Regiment was ordered to take part in the occupation of the city. Middleton's landing party went in unopposed and settled into occupation duty without a shot being fired. Middleton spent a total of seven months in Mexico and returned home to Galveston in November 1914.[26]

Marriage

[edit]After arriving at Fort Crockett, Middleton adapted to garrison life and attended Saturday night dances in town. At one such dance he had a navy lieutenant introduce him to Jerusha Collins, who would later become his wife. She had attended Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, and had made her debut in Galveston society in 1911. Following the death of her father, Sidney G. Collins, Jerusha had come to live with her aunt and uncle, Mr. and Mrs. John Hagemann, in Galveston. As a merchant, Hagemann was well to do. Middleton met the Hagemanns, soon becoming a regular visitor at their house while calling on Jerusha.[27]

Following seven months in Mexico, Middleton's return to Galveston brought a special anticipation. He had proposed to Jerusha Collins at an earlier time, and renewed the proposal upon his return. The couple was married on 6 January 1915, and this allowed them to be in New Orleans two days later with other members of Middleton's unit for the one hundredth anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans in which the 7th Regiment had served. After a week in New Orleans, the couple returned to Galveston, and were invited to move into the Hagemann's house, where they were given a large upstairs room.[28]

Fort Bliss

[edit]

When Galveston's second major hurricane hit the Texas coastline in mid-August 1915, most of the Army units had scattered to safe locations away from the storm's path, with a few units remaining in the secure buildings of Fort Crockett or in downtown Galveston. The Middletons chose to ride out the storm at the Hagemann house. Following the storm cleanup, in October 1915, the 7th Regiment was ordered to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas as events in Mexico flared up again. Here they were put under the command of Brigadier General John Pershing, a highly capable officer who had skipped three ranks by being promoted from captain to brigadier general for his exceptional service during the Philippine–American War.[29]

The Mexican Revolutionary General Pancho Villa, who had at one time been supported by the United States, felt betrayed when the Americans backed Carranza. In January 1916, Villa's followers, known as Villistas, attacked a train and killed 16 American businessmen. Two months later Villa's men crossed the border into the United States and attacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico, killing an additional 19 Americans. Following these attacks, General Pershing took his forces into Mexico to pursue Pancho Villa.[26]

Preceding these events, Middleton's 7th Regiment was sent to Camp Harry J. Jones near Douglas, Arizona to perform border security.[30] While there, Middleton and a squad of his men were fired upon by the Villistas who unsuccessfully attacked the Mexican village of Agua Prieta, across the border from Douglas.[30] While several of Middleton's men were hit, no one was killed, and they all returned with the 7th Regiment back to Fort Bliss in late December 1915.[31]

Preparation for war

[edit]The hunt for Pancho Villa ended unsuccessfully for the Americans. War was raging in Europe, and following several months in Mexico, Pershing was called back to Fort Bliss to begin preparing his troops for this much larger conflict. In April 1917, President Wilson requested that Congress declare war, which they did. The same month Middleton was assigned to Gettysburg National Park where the 7th Regiment would continue its training. Here, he was promoted to first lieutenant on 1 July 1916, after a little more than three and a half years as a second lieutenant.[32] With the pending war, his promotions would become much more frequent, and in less than a year he was promoted to captain, on 15 May 1917, over a month after the American entry into World War I.[32]

World War I

[edit]In preparation for its buildup in strength, the army had to train a large cadre of officers. On 10 June 1917 Middleton was assigned to Fort Myer, Virginia, as the adjutant of a reserve officer training camp. These camps were organized to take civilians and turn them into officers in ninety days, and as adjutant Middleton was responsible for directing the flow of paperwork for 2,700 officer candidates. By November 1917, his camp graduated its last class of officers, and Middleton requested to join a combat division. His request was granted and on 21 December 1917 he reported to the 4th Division at Camp Greene near Charlotte, North Carolina. Two days later, however, he received new orders to become the commander of a reserve officer training camp in Leon Springs, Texas. Here, he reported as ordered, and stayed until the mission was complete in April 1918. As he was technically on loan from the 4th Division, his request to rejoin that unit was granted, and Middleton was soon on his way to France.[33]

Believing that the 4th Division was still at Camp Greene, Middleton wired there to find out that the unit was already on its way overseas. He caught a train for New York, and when he arrived on 28 April 1918, he found his division at Camp Mills on Long Island, living in tents and awaiting transport. Middleton was given command of the First Battalion, 47th Infantry Regiment, and departed New York with his regiment aboard the Princess Matokia on 11 May in a convoy of fourteen ships. Three days out of France, a fleet of destroyers met the convoy and escorted it to the port city of Brest where they arrived on 23 May. There the division unloaded and organized for several days, subsequently loading onto a troop train to arrive at Calais on 30 May.[34]

Calais, Chateau Thierry and Saint-Mihiel

[edit]

The first assignment of the 4th Division was to become a reserve unit for the British, just south of Calais. The Americans gave up their Springfield Rifles for some British Enfields for which there was available ammunition. When the Germans began an offensive north of Paris, the 4th was put onto trains and sent to the Marne River, about twenty-five miles west of Chateau Thierry. Here the 4th became a reserve unit for the badly battered 42nd Division.[35] In late July 1918, Middleton, promoted to major on 7 June, moved his First Battalion in to support the 167th Regiment of the 42nd Division. In the ensuing operation, called the Second Battle of the Marne, four days of heavy fighting took place against the Prussian Fourth Guard Division fresh from a month's rest. While the veteran Germans fought with determination, the Americans were able to push them back about twelve miles, though at a considerable cost—more than one in four of the Americans became casualties.[36]

When the 4th Division was relieved, they were sent to the Saint-Mihiel area, where they would undertake a small support role. Major Middleton was given the task of directing the unit's transport, complicated by the requirement to move at night with equipment and personnel to be drawn by horse and mule. After Saint-Mihiel, the unit was moved to Verdun where hundreds of thousands of French and Germans had become casualties earlier in the war. This would become the last major engagement of the First World War for Middleton, who was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 17 September, shortly before the commencement of the operation, called the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.[37]

Meuse-Argonne Offensive

[edit]

The 4th Division, on its own for the first time in the war, was assigned a front that was one to two miles wide, sandwiched between two seasoned French divisions, about eight miles from Verdun. Lieutenant Colonel Middleton's battalion led the attack for the Americans on 26 September 1918. That day, they covered five miles, breaking through German defenses, after which it was up to the entire 47th Infantry Regiment to hold onto the gains.[38] Middleton then put his second-in-command in charge of the battalion when he was assigned as the executive officer of the regiment. He was in this staff position for two weeks when, on 11 October, he was given command of the 39th Infantry Regiment after commander James K. Parsons and most of his regimental staff became casualties following a gas attack.[39] At about one o'clock in the morning, Middleton had to find his way to the 39th headquarters and prepare for battle at daybreak. Shortly before 7:30 a.m., Middleton led his new regiment into enemy-held territory using a tactic called "marching fire," where all of the troops constantly fired their weapons while moving a mile through heavy woods. This compelled most of the dug-in and concealed Germans to surrender, and allowed the 4th Division to move to the edge of the Meuse River.[40] Three days after taking command of the 39th, and two days after his twenty-ninth birthday, Middleton was promoted to colonel, becoming the youngest officer in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to attain that rank.[40] He also received the Army Distinguished Service Medal for his exceptional battlefield performance.[41] The citation for the medal reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Colonel (Infantry) Troy Houston Middleton, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, in a duty of great responsibility during World War I. As a battalion and a regimental commander of the 47th Infantry, 4th Division, Colonel Middleton gave proof of conspicuous energy and marked tactical ability. He achieved notable successes in the operations near Sergy, along the Vesle River, and during the fierce fighting in the Bois-du-Fays and the Bois-de-Foret of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, rendering invaluable services to the American Expeditionary Forces.[42]

On 19 October, the 4th Division was withdrawn from the battle line after 24 days of continuous contact with the enemy, the longest unbroken period of combat for any American division during the war.[43] Middleton was now given command of his former regiment, the 47th. In early November the 4th Division relieved an African American regiment near Metz, and was preparing to chase German defenders down the Moselle River, with Middleton to lead the attack. The attack did not materialize, however, because, on 10 November, Middleton received confidential news that an armistice was imminent. The following morning a messenger brought word that there would be no more firing after 11 a.m. There was celebration throughout the ranks, but there was still much work to be done; the 4th Division would soon be assigned to Germany as an occupying force.[43]

Occupation of Germany

[edit]In late November 1918 the 4th Division began a road march of more than 125 miles from the French city of Metz toward the German city of Koblenz, on the Rhine River. The final destination of Middleton's 47th Regiment would be the town of Adenau, 35 miles due west of Koblenz. The road trip took fifteen days of moving through almost incessant rain and ended in a driving snowstorm on 15 December. Middleton rode a horse during most of each day, surveying his troops and occasionally dismounting to talk with them. The formation marched for fifty minutes of each hour, and rested for ten, with a full hour for lunch.

Once in Adenau, the regiment dispersed to many villages in the area, while Colonel Middleton stayed in a large home in Adenau where the owners continued to live as well. During the stay in Adenau, the 47th continued with its training, building a rifle range, running combat problems, and practicing lessons learned from its recent combat operations. In early March 1919, after nearly four months in Adenau, the 47th was ordered to the area of Remagen on the Rhine. On the morning of the move, Middleton had breakfast with Colonel George C. Marshall, who had come to Adenau the day before to inform Middleton of his regiment's new orders. Marshall was the aide of General John Pershing, who by now was the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the AEF.[44]

At Remagen the 47th Regiment was given the mission of guarding the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine River. Twenty five years later the 47th would once again guard this bridge during World War II. The regiment remained here until given orders to return home in mid-summer 1919. Before his departure from Europe, Middleton was summoned to report to the Third Army Chief of Staff in Koblenz. Here he was informed that he and other senior officers were being assigned to Camp Benning, Georgia, to form the first faculty of the Infantry School that was being established there. Middleton sailed out of Brest in mid-July, met his wife in New York, and together they traveled to Columbus, Georgia, by way of Washington, D.C., and Atlanta.[45]

Military schools

[edit]For the ten years following World War I, Troy Middleton would be either an instructor or a student in the succession of military schools that Army officers attend during their careers.[46] Middleton arrived in Columbus, Georgia with strong praise from his superiors, and would soon get his efficiency report, in which Brigadier General Benjamin Poore of the 4th Division wrote of him,

The best all-around officer I have yet seen. Unspoiled by his rapid promotion from captain in July to colonel in October; and made good in every grade. He gets better results in a quiet unobtrusive way than any officer I have ever met. Has a wonderful grasp of situations and a fine sense of proportion.[47]

Infantry School

[edit]Up until the World War, other branches of the Army had their own specialty schools, but the infantry did not. This situation was being amended, and Middleton would be part of that change as a new faculty member of the Infantry School at Camp Benning, about nine miles from Columbus.[48] Middleton, whose rank had reverted to his permanent rank of captain following the war, was an instructor in the new school for his first two years at Benning, and also a member of the Infantry Board, set up for research on weapons and tactics. One of his jobs on the board was to evaluate new weapons and equipment, and at one point he tested a new semiautomatic rifle which would eventually become the M-1 rifle, the standard weapon of the infantry in World War II.[46]

The first nine-month class of the new infantry school began in September 1919, and students were taken through a curriculum of weapons and tactics. Captain Middleton, the youngest faculty member on the school staff, was an ideal instructor, fresh with experiences from the recent war.[49] After two years as an instructor, and a promotion to major on 1 July 1920, Middleton prevailed upon his commanders to be allowed to enroll in the advanced infantry course as a student. This ten-month course included instruction on combined arms, tactical principles and decisions, military history and economics, then ended with a written thesis. Middleton, who was one of the most junior members of his class, finished at the top of the class.[50]

Following the advanced course, Middleton spent the summer as the senior instructor at a Reserve Officer Training Camp at Fort Logan, Colorado, then returned to Camp Benning for one more year as a member of the Infantry Board. Four years at Benning had been enough for him and he was ready to move on. After expressing his wishes to a senior officer, he was assigned to Fort Leavenworth in the summer of 1923.[51]

Command and General Staff School

[edit]

As one of the youngest majors in the army, Middleton found himself among officers who were ten to fifteen years his senior at the Army's Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Students attended this ten-month school to qualify for higher commands.[52] Here Middleton met a classmate, George Patton, who would become one of his friends. Patton had confided to Middleton that he predicted completing the course as an Honor Graduate, one who finishes in the top 25% of the nearly 200 students. His prediction came true, and he finished 14th in the class. Middleton finished 8th.[52] With his exceptional class performance, Middleton, along with half a dozen other graduates, was invited to stay on for the next four years as an instructor at the school.[53]

During his second year of teaching at Command and General Staff School, one of his students, Dwight D. Eisenhower, would come to his office and pump him for information, knowing that Middleton had commanded a regiment in combat in France. Eisenhower asked practical questions, and was unquestionably motivated—he finished first in his class.[54] Nearly every officer who commanded a division in Europe during World War II attended the Command and General Staff School during Middleton's tenure there from 1924 to 1928. There was also a point in time during World War II when every corps commander in Europe had been a student of Middleton's.[54]

War College

[edit]In 1928, his final year at Leavenworth, Middleton received orders to attend the Army War College in Washington, D.C. His year at this highest level of professional military education was very fulfilling. He spent time in the school library and the Library of Congress.[55] He wrote his staff memorandum (equivalent to a thesis) on the subject of Army transportation. Recalling his personal experience with horses and mules in France, he recommended that motorized transport significantly replace the Army's use of livestock. The commandant of the school commended Middleton for work of exceptional merit, and sent his ideas to the highest levels in the War Department.[56]

Late career

[edit]Having spent the previous ten years in the various Army schools, Major Middleton requested a return to Camp Benning, where he and his wife still had friends. The request was approved and he was assigned as a battalion commander in the 29th Infantry Regiment there, the same unit in which he had enlisted nineteen years earlier at Fort Porter.[57] He was at Benning for only a year when he was told he would be assigned to the General Staff at the War Department in Washington D.C., but this changed when a new requirement for career officers was brought to his attention. Officers were now expected to have an assignment with a civilian component of the Army such as the National Guard, the Reserves, or the Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC). The last option appealed to Middleton the most, and he wanted to work at a school in the south. There was an opening at Louisiana State University (LSU), and this is where Middleton soon headed.[58]

ROTC duty at Louisiana State University

[edit]In July 1930 Troy Middleton stopped at his new headquarters at Fort McPherson in Atlanta, then drove west with his family to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which would become the family home for many years. Major Middleton became the Commandant of cadets at LSU, along with being the professor of military science.[59]

While at headquarters, Middleton had learned that his predecessor did not get along with Louisiana's governor, Huey P. Long. Middleton was told a few stories about the governor that made him curious enough to call on him the day after arriving in town. While the meeting turned out to be somewhat awkward for Major Middleton, it began a friendship between the two men.[60] Governor Long loved LSU and the cadet corps there. When Middleton mentioned to him that the cadet band had just a few dozen members, the governor saw to it that the band would grow to 250 members. Governor Long was a showman, and enjoyed parades and fanfare, and would negotiate special fares to get the cadets and band transported to athletic events across the region.[61] Because of the governor's dealings, LSU transformed from a third rate school in 1930 to the largest university in the south by 1936.[62]

During Middleton's tenure at LSU the presidency of the university changed hands from President Atkinson to President James Monroe Smith, the latter an appointee of Governor Long. Towards the end of Middleton's fourth year on campus President Smith asked him if he would stay on for an additional year and also become Dean of Men. Middleton responded that he would accept, but it had to be cleared through the War Department. Smith's request to the War Department for both the extension and the deanship for Middleton were approved. Toward the end of the fifth year Smith went a step further, suggesting that Middleton retire from the army and become a permanent member of the LSU staff. Middleton would not even consider retirement, but accepted a sixth year with the ROTC program. As he began his sixth year on campus, on 1 Aug 1935, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel.[62]

Early in his final year on campus, Middleton was once again pressed by the university president to retire from the army and go to work for the college. Again, Middleton could not do that, and began looking for a suitable follow-on assignment. Not having been overseas in over sixteen years, he put in a request for duty in the Philippines. He finished his tenure at LSU in the summer of 1936, having overseen the increase in students completing the ROTC program from about 500 to over 1700 cadets.[62]

Philippines and retirement

[edit]

In August 1936 the Middletons made a leisurely drive to New York City where they boarded a ship for the Philippines. The trip took them 42 days and included passage through the Panama Canal with stops in Panama, San Francisco, Hawaii, and Guam. When they arrived in Hawaii, they were greeted by George Patton and his wife Bea. Patton was on duty in Honolulu and had sailed his own boat from San Diego to Hawaii, and later sailed it back to the states at the end of his tour.[63]

Middleton was assigned as an assistant inspector general in the army headquarters in Manila. Here he listened to complaints as he travelled to various Army installations including Fort William McKinley and Corregidor.[64] Less than six months into his Philippine tour he received a telegram from President Smith renewing his offer of a job at LSU as the dean of administration with a salary of $5,400 per year. Middleton was in the hospital undergoing testing for some heart irregularity when the telegram arrived, and he showed it to two other lieutenant colonels who were visiting him. One of them said he should take the offer, the salary being excellent. The other lieutenant colonel, Dwight Eisenhower, said he should stay in the army. Eisenhower had spent three years in Panama as an aide to General Fox Conner, who knew that the terms of the Treaty of Versailles were being ignored by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, and who was certain another war was coming soon. Eisenhower reasoned that this was no time for an officer with Middleton's combat experience to be getting out of the Army.[65]

To Middleton, as a very junior lieutenant colonel, the prospect of becoming a general officer seemed very remote, and upon giving the matter more thought he ultimately decided to retire from the army. Once his decision was made, he wired President Smith at LSU advising him that he was ready to become a civilian and accept the university post.[66] The Middletons left the Philippines in May 1937, stopping in Hong Kong, Japan, and China en route to San Francisco. Lieutenant Colonel Middleton officially retired from the army on 31 October 1937.[67]

Tenure at Louisiana State University

[edit]The first year in his new job as administrative dean at Louisiana State University (LSU) went smoothly. The Middletons had a new house built on Highland Road near the campus, and an oil field was discovered under their property, bringing them royalties that would pay for their property many times over. University enrollment began to climb in 1938 and the LSU football team had just finished three outstanding seasons under coach Bernie Moore, winning 27 of their 30 regular season games. Middleton was photographed breaking ground for a new faculty club that year, as the campus grew in many areas.[68] All seemed to be running well when in June 1939 the campus was given a shock from which it would take many years to recover. A New Orleans newspaper ran a photo on the front page showing an LSU truck unloading building materials in suburban New Orleans, revealing an illegal operation. The ensuing investigation led to the discovery that LSU's President Smith had embezzled nearly a million dollars from the university, using the money to cover his losses while speculating in the Chicago wheat futures market. Smith stood trial, and was sent to first Federal prison and later the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola.[69] The LSU superintendent of grounds and buildings, George Caldwell, was also involved in the scandal and served time in Atlanta for tax evasion. Meanwhile, the state's governor, Richard Leche, resigned, but was soon found guilty of several federal charges and sent to Atlanta to serve time.[69]

The Board of Supervisors met in a special session at the end of June 1939 and Middleton was directed to take over the business management of the university. The school's finances were in a state of chaos, and it would take effort and time to dig out of the mess. The dean of the Law School, Paul M. Hebert, became the acting president, and Middleton became acting vice president and comptroller. Middleton chose two accounting professors, Dr. Daniel Borth and Dr. Mack Hornbeak, to work with him, and a New York firm was hired to come in and establish sound business procedures.[70]

Before the revelation of the illegal activities, expenditures had been routinely made on a cash basis, all of the university funding and program money was thrown into a single account, and university bond indentures had been violated. The new leadership had to advertise in Louisiana newspapers to find out to whom they owed money. The first year of dealing with the situation required 16- to 18-hour days, six days a week, and after that the process still required overtime through the year 1941. Faculty and staff members, accustomed to making purchases without bids, purchase orders or knowledge of the budget, had to be educated on the accepted business procedures on which the rest of the world operated.[71]

While Middleton was helping LSU recover from this ordeal, he was also keeping an eye on events in Europe. In July 1940 he wrote a letter to General George Marshall asking if his services were needed by the Army as the United States was making preparations for war. Marshall replied that as much as the Army would like to have Middleton back in uniform, all the Army could do would be to place him in some training role, which would not effectively use his battle experience.[72]

Middleton stayed at LSU until 1942, describing his days as the comptroller of LSU as long days that he would not want to relive, but after the first year he found both the work and his association with Hebert, Borth and Hornbeak to be satisfying and rewarding. He felt that during this period of time he was able to make his greatest contribution to an institution that had been very good to him in the past.[73]

World War II

[edit]Troy Middleton was out dove hunting with his son, Troy Jr., and a friend on Sunday morning, 7 December 1941. Having had a successful morning, the trio decided to take a break for lunch, then come back out and get their bag limits in the afternoon. When they arrived at home for the mid-day meal, Mrs. Middleton greeted them with the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. This put an end to the dove hunting, and Troy Middleton began to make plans.[74] The next day he reported to the LSU president announcing his intention to offer his services to the U.S. Army, and he sent a telegram to the War Department announcing his availability for service. Within a day or so he received a reply: he would report to active duty as a lieutenant colonel on 20 January 1942.[75]

Middleton was assigned to a training regiment at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, where he was quickly promoted to colonel on 1 February, and oversaw the combat training of thousands of recruits.[75] After less than two months, he was given a rapid succession of assignments, including to Camp Gordon, Georgia and Camp Blanding, Florida. While at Blanding he was called to the War Department in Washington, where he was given an assignment to be a staff officer in London, but this rapidly changed when he was called to the War College, and met a classmate from Command and General Staff School, Brigadier General Mark Clark, who told him that he was being assigned to the Forty-fifth Infantry Division at Fort Devens, Massachusetts.[76]

45th Infantry Division

[edit]

Upon returning to Florida in early June 1942 to pick up his personal effects, Middleton received his orders for Fort Devens, and also word that he had been promoted to brigadier general. In mid-June he reported to the 45th, known as the "Thunderbirds," an Army National Guard division consisting mostly of troops from Oklahoma, but also including some from Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. The commanding general of the 45th, Major General William S. Key, anticipated being replaced with an active duty officer. Though Middleton was not informed of this, in late summer 1942 Key was replaced, and Middleton was given the command of the division, along with a promotion to major general.[77]

In the summer, the 45th did its training at Cape Cod, Massachusetts, after which Middleton was in command for winter training at Pine Camp, New York. Here the temperature dipped to −36°F and snow drifted head-high. A soldier in the division by the name of Bill Mauldin did a cartoon showing slop from the kitchen frozen in a column as it descended into the garbage can outside. Mauldin later became famous for his cartoons during World War II, and won two Pulitzer Prizes for his work.[78] In February 1943 the training moved from Pine Camp to Camp Pickett, Virginia, for mountain training, and then to the Atlantic Coast for ship-to-shore training between Norfolk, Virginia and Solomons, Maryland. In early April, while the division was at Camp Pickett, Middleton was sent to North Africa with some of his staff to begin planning the ensuing military operation. Here he went to the headquarters of the Seventh Army commander, Lieutenant General George S. Patton, in Morocco and stayed nearly a month. Patton would command the Seventh Army in the Sicily landings during the summer, and the 45th would be the only combat-loaded division coming from the United States. With the division scheduled to sail from Norfolk on 5 June, Middleton left beforehand to complete the planning for the landing on a hostile shore, this time reporting to the II Corps headquarters of Lieutenant General Omar Bradley in Algiers, Algeria. For this operation, Bradley was subordinate to Patton, under British overall direction. By the time the division arrived in Oran, Algeria, the planning was complete, and the unit was able to run one rehearsal in western Algeria before embarking for Sicily.[79]

Sicily

[edit]The 45th Division was under Omar Bradley's II Corps, which in turn was subordinate to Patton's Seventh Army. Overall command of the Sicilian invasion, called Operation Husky, was with British General Sir Harold Alexander, and the British forces were organized under the British Eighth Army commanded by General Bernard Montgomery. The 45th Division consisted of three infantry regiments, the 157th, 179th and 180th, and numerous other elements. Fighting alongside the 45th Division were the First Infantry Division, Third Infantry Division, and the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) (with the 3rd Battalion of the 504th PIR and numerous other support units attached), part of the 82nd Airborne Division.[80]

The 45th departed Oran on 4 July 1943, with little attention paid to the fact that it was Independence Day.[81] The six-day trip to Sicily was smooth at first, then turned fairly rough, with seasickness prevalent among the troops. The weather calmed as several troop ships rendezvoused near the town of Scoglitti, on the western side of Sicily's south coast. At 2 a.m. on 10 July the landing craft were filled with infantrymen, and as the craft approached the shoreline, the Navy opened up with a volley of preparatory fire.[82] The primary mission of the 45th was to capture two airfields needed for Allied aircraft.[83] Comiso Airfield, about eleven miles from the shore, was captured in a day and was being used by American planes the next day. It took four days for the division to capture Biscari Airfield, about twelve miles inland.[83]

The next objective of the 45th was to fight German and Italian forces en route to the north coast of Sicily. The plan was to use Highway 124, one of Sicily's four major highways. This highway, originally in the American sector, had been usurped by Montgomery, with no word of the change of boundaries given to Middleton.[84] Word eventually came down from Alexander that the boundaries had been changed, which meant that when the 45th reached the highway, they became frozen in place with no opportunity to advance. Middleton moved his division from the right of II Corps to the left, traveling ninety miles out of the way through back areas of the other American divisions, to get in position for the march north.[85] On 23 July the first elements of the 45th reached the north coast of the island at Station Cerda, five miles east of Termini Imerese, taking thirteen days to move from south coast to north coast. The division then moved east along the coast, reaching its objective of Santo Stefano on 30 July. Here they were stormed by the Germans, but fought back, forcing the German rear guard out of the area by the following morning. This was the end of active fighting for the 45th in Sicily, where the division endured 1,156 casualties while taking nearly 11,000 prisoners.[86]

The Third Infantry Division was moved in to replace the 45th, which was now ticketed for the upcoming invasion of the Italian mainland.[87] In recalling events on Sicily in his biography, Middleton noted a strain in his relationship with General Patton. Patton felt that the Mauldin cartoons published in the division newspaper were irreverent and unsoldierly. Middleton consistently defended Mauldin, but was verbally ordered by Patton to get rid of him. When Middleton told Patton to put the order in writing, the issue was dropped.[88] Soon thereafter, Patton slapped two soldiers who he suspected of malingering in hospitals, which brought public condemnation and loss of his command.[88]

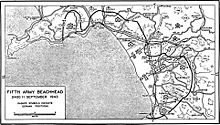

Italian mainland

[edit]The month of August 1943 was used by the 45th Division for some rest and planning. Seven plans for the invasion of Italy were put on the table, and three of them were adopted, of which the British had two (Operation Baytown and Operation Slapstick) and the Americans had one, called Operation Avalanche.[89] The 45th Division would be under Major General Ernest J. Dawley's U.S. VI Corps, within the U.S. Fifth Army commanded by Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark. The plan called for the landing of the Allied forces in the vicinity of Salerno, Italy, about 200 miles north of Sicily.[90]

The first Allied landings on the beach occurred on 9 September, with two regiments of Middleton's 45th Infantry Division, the 157th and 179th Infantry, landing the following day. The other regiment of the division, the 180th, would land at a different point and be held in reserve by Clark.[89] Middleton was responsible for ten miles of beachhead between the British X Corps and the U.S. 36th Infantry Division. The German defensive positions pounded the Allies, who gained little ground in the first few days of the operation. Lieutenant General Clark, the Fifth Army commander, faltered and sent around a confidential memo indicating that he was contemplating taking the troops back off the beaches.[91] Middleton, telling his staff that they were not leaving, spread around the word to his troops that it was a good time to do some hard fighting.[91] On the morning of 14 September units of the 45th did some particularly hard fighting at a large tobacco factory, consisting of five imposing stone buildings in a somewhat circular pattern. The Germans were dug in here, and repulsed the Americans initially, but with the aid of some naval gun fire, the Germans were eventually pushed back. Clark visited the front later that day, and was convinced that his army was going to stay.[92]

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, now the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, visited the beachhead on 17 September, observing that the battle had been won. The following day the Germans had pulled out of the area, and the 45th was able to advance to Venafro before meeting any resistance.[92] The division was at the far right of the Fifth Army, working up the center of the Italian boot, adjacent to Montgomery's British Eighth Army which was responsible for the eastern half of the boot. By 24 September the division had taken Oliveto and Quaglietta after some heavy fighting, and by 3 October they had taken Benevento.[93] On 21 October the division was put into corps reserve, following almost six weeks of uninterrupted action. There was still some German resistance around Venafro, and elements of the 179th Infantry Regiment secured the town on 2 November. With this the fighting came to a large pause as Allied planners studied further action.[94]

With the lull in the fighting, and the onset of autumn rains, coupled with endless hills and deepening mud, Middleton's left knee, which had been uncomfortable for more than a year, was now becoming agonizing. He had hurt his right knee many years earlier playing football, but there was no immediate explanation for the pain in his left leg. Medics studied his leg, but had no answers.[95] In late November Middleton went to the hospital in Naples, staying well into December, still without adequate diagnosis. He was able to hobble around, and did some staff work, then flew to General Eisenhower's headquarters in North Africa. He stayed there until mid-January, when he was sent to Walter Reed Hospital back in the United States.[96] While Middleton was at Walter Reed, General Eisenhower communicated to General George Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, that he needed Middleton back overseas. Acknowledging Middleton's difficulty with his knees, Eisenhower said, "I don't give a damn about his knees; I want his head and his heart. And I'll take him into battle on a litter if we have to."[97] Command of the 45th Division went to Major General William W. Eagles.

The two generals came up with a plan, and Middleton was sent to six Army installations in Tennessee, Colorado, and Washington, D.C., with a brief stopover to visit his family in Baton Rouge. Middleton would be taking command of VIII Corps in England, and was sent to the various locations to confuse the enemy about the personnel change. Accompanying him was a sergeant who had been a physical therapist in civilian life, and who would massage Middleton's knees twice a day for the next year. When asked what staff he needed to take with him, Middleton replied that he would keep the staff that was already in place, except that for an aide he would like his old LSU friend, Mack Hornbeak, who had served with him through Sicily and Italy.[98]

VIII Corps

[edit]

The U.S. VIII Corps had arrived in the United Kingdom in December 1943, and was commanded by Major General Emil F. Reinhardt, who Middleton had known for many years. While he was an able commander, his lack of combat experience resulted in his being replaced by Middleton (though Reinhardt would later command a division in the European fighting). Middleton's first stop in Europe before assuming command of VIII Corps was to confer with his friend and commander, Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower had asked Middleton about his views on making Patton the commander of an army. Middleton thought it was a good idea since Patton was such an able fighter. Eisenhower agreed, but was concerned about Patton's propensity to embarrass the Army by things he said to the press. Following this Patton was given command of the Third Army, which was headquartered north of London during the preparation for the invasion of Normandy.[99]

Middleton's VIII Corps headquarters was in the town of Kidderminster about fifteen miles from Birmingham, and about 110 miles northwest of London.[100] In order to deceive the Germans, Middleton moved his headquarters another 75 miles to the north, near Liverpool. This made it appear that the corps would move east to the English Channel for a landing near Calais, France. The ruse was effective, keeping the Germans guessing, and compelling them to split their forces among multiple locations along the French coast, instead of concentrating their forces at one probable landing point.[101]

The VIII Corps fell under Patton's Third Army, and trained in England from March to late May 1944. Two weeks before the invasion, the corps was pulled out of the Third Army and placed in Omar Bradley's First Army. First Army was responsible for the D-Day landings in Normandy, and once the Allies were established on shore, Middleton was to bring his VIII Corps across. Shortly before the invasion, Middleton took his corps to Southampton where they awaited their channel crossing time.[102]

Cotentin Peninsula and Operation Cobra

[edit]The VIII Corps sat in Southampton from D-Day, 6 June, until 11 June 1944 when it began crossing the English Channel.[103] The corps lost only one of its Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) to a mine during the crossing, but on it was about half of Middleton's headquarters complement. Other than the members of the sunken LST, who would rejoin the corps ten days later, the entire corps was ashore on 12 June near Carentan, where Joe Collins' VII Corps had cleared the beach on D-Day.[103] At this point the divisions of VIII Corps included the 82nd Airborne, 101st Airborne, 79th Infantry and 90th Infantry. The 82nd, under Major General Matthew Bunker Ridgway, performed admirably, but soon left the corps, and once in Brittany the corps would have an entirely different complement of divisions.

After VII Corps took the port city of Cherbourg, VIII Corps began moving south against German forces in the middle of the Cotentin Peninsula. The Germans had the high ground, and the fighting was further complicated by the bocage countryside—a series of farmers fields and pastures forming a latticework, with each unit separated by walls of earth up to six feet high supporting dense shrubbery and trees.[104] The German defenders had every advantage over the Americans, whose tanks would tip up and expose their thin bottom armor as they attempted to cross the barriers. By mid July, field expedient devices were developed to equip tanks to penetrate the hedgerows and restore battlefield mobility. Such specially equipped tanks were referred to as Rhino Tank.[104]

After breaking out of the bocage, VIII Corps was able to roll fifty miles in seven days, but it, and the remainder of Bradley's First Army, remained bottled up on the Cotentin Peninsula.[105] The next phase of the fight, codenamed Operation Cobra was to break out of the peninsula, and once this occurred, Patton's Third Army would join the fight. The operation began on 24 July 1944 when American air commanders were asked to lay a carpet of bombs on the Germans to soften them up for the advancing ground forces. Poor weather curtailed the operation on the first day, but more than a thousand bombing missions were carried out the following day. Lieutenant General Lesley McNair, chief of the Army Ground Forces, came to Middleton's headquarters to witness the bombing. Middleton warned him to stay at corps headquarters, but McNair strayed away far enough that he and other members of his party were killed when they got caught by Allied bombs. More than 600 U.S. troops were killed or wounded in this friendly fire incident when the bombs fell short of their intended target.[106]

Despite the mishap, the bombing was effective in reducing the German resistance, and over the next few days the VIII Corps was able to move south along the coast. On 30 July they seized the town of Avranches, the gateway to Brittany and southern Normandy.[107] Once in command of Avranches, VIII Corps then secured the bridges at Pontaubault, and in doing so, broke out of the Cotentin Peninsula and into Brittany. This brought about the planned command change, and at noon on 1 Aug 1944 Omar Bradley moved up to command the 12th Army Group, Courtney Hodges took over the First Army, and Patton's Third Army was activated into the group along with First Army, with Middleton's VIII Corps now falling under General Patton.[108]

Following the breakout, Middleton found himself in a doctrinally uncomfortable situation, as the allies were now in a position to pursue the Germans. The cautious and methodical Middleton was in command of two infantry divisions and two armored divisions within his corps, and the impatient Patton could not understand why Middleton was not pursuing.[109] In early August Patton wrote in his diary, "I cannot make out why Middleton was so apathetic or dumb. I don't know what was the matter with him." Despite his wealth of battlefield experience and years of military schooling, Middleton had only limited experience in conducting pursuit operations, and was a bit overwhelmed by them.[110] Ultimately he allowed his armored divisions some autonomy in their operations, while using his infantry to clean up pockets of resistance en route to Brest.[111] His estimates of enemy strength turned out to be much more accurate than those provided to him by Patton, and Patton ultimately acknowledged Middleton's value as a corps commander by presenting him with a Distinguished Service Medal within seven weeks of calling him "dumb" in his diary.[112]

Battle for Brest

[edit]After the breakout from the Cotentin Peninsula, VIII Corps followed the Brittany coast westward en route to Brest, the port of Middleton's arrival and departure from Europe during World War I. As the corps passed St. Malo, Middleton turned his 83rd Division on the town, resulting in the capture of 14,000 Germans following a lengthy battle.[113] Patton had already directed the corps' 6th Armored Division under Major General Bob Grow to move on to Brest while Middleton was still cleaning up in St. Malo, which fell on 17 August. Grow had arrived outside of Brest on 7 August, and met stiff resistance once there.[114] The city, housing important German submarine pens and extensive machine facilities, was defended by three elite German divisions and several powerful 90-millimeter guns which were capable of destroying most of the armor in the 6th Armored Division. The siege of Brest required infantry, and once the 2nd Infantry Division under Major General Walter M. Robertson arrived, the armored division was released back to Patton for other operations. Also joining VIII Corps for the siege was the 8th Division commanded by Major General Donald A. Stroh and the 29th Division, a National Guard unit from Virginia, commanded by Major General Charles H. Gerhardt. Middleton also had a cavalry group and two ranger battalions commanded by Colonel Earl Rudder who later became president of Texas A&M University.[115]

The city was well organized for defense, and in the Battle for Brest Middleton's units went about capturing it methodically. The defense of the city was under German Generalleutnant Hermann Ramcke with whom Middleton carried on a dialog during the siege. Ramcke sent Middleton a map showing where several hundred American prisoners were being held in the city, but also placed on the map a number of red crosses where the Allies knew some good bombing targets were located, such as ammunition depots.[116] Middleton wrote back to Ramcke telling him to remove some of the bogus red crosses, or some terms of the Geneva Convention might have to be ignored. Middleton also reminded Ramcke of the Allies' superior artillery and air power.[117]

The battle for Brest was intense and very destructive. After two weeks of constant day and night attacks, Middleton's units forced the Germans into ever tighter positions.[117] On 12 September, Middleton sent a letter to Ramcke offering him an opportunity to stop the bloodshed, and to surrender the city in a humane and reasonable way, with terms of surrender spelled out in the letter. Ramcke's terse reply was simply, "I must decline your proposal."[118] Unhappy with the response, Middleton directed his soldiers to "enter the fray with renewed vigor...take them apart—and get the job finished."[118] One week later, on 19 September, the Germans surrendered to Middleton, who, with much of his staff, had 99 unbroken days of combat. In a formal ceremony, Middleton gave the city back to its mayor, and General Patton arrived to pin a Distinguished Service Medal oak leaf cluster on Middleton for outstanding conduct during the campaign in Brittany, resulting in the capture of Brest.[112]

The Americans captured more than 36,000 Germans, and evacuated 2,000 wounded, far exceeding the estimate of 10,000 Germans given to Middleton by Patton before the operation.[112] Ramcke was captured by troops of the 8th Division, and asked the deputy division commander for his credentials. The American general pointed to the M-1 rifles being carried by his soldiers and told Ramcke that those were his credentials.[112] Ramcke appeared at his formal surrender clean shaven and with a well-groomed Irish setter. With plenty of reporters and photographers documenting the occasion, Ramcke commented in English that he felt like a film star. He was soon sent to a prisoner of war camp in Clinton, Mississippi. After the war he spent time in a prison camp in England, and then was sent to France where he was tried and found guilty of war crimes against French civilians during the fighting at Brest. Ramcke continued a correspondence with Middleton for 15 years following the war.[119]

Move to the Ardennes

[edit]

With western France in the hands of the Allies, in late September Middleton made a leisurely trip east across France to the Ardennes Mountains, stopping en route to visit battlefields where he had served with distinction in 1918 during the Great War.[120] The Germans were now behind a line from west of Metz, France, through Luxembourg, and east of the Belgian cities of Bastogne, Liege and Antwerp. The Allies had outrun their supply lines and had to slow their advance to resupply.[121]

Middleton's VIII Corps was assigned a 50-mile front, half of which belonged to the 2nd Division and the other half to the 8th Division. The front extended from Losheim, on the German-Belgian border, to central Luxembourg. On 11 October, the 83rd Division was brought back under VIII Corps control, and another 38 miles of front in Luxembourg was added to the responsibility of the corps. The new 9th Armored Division was added to the lineup on 20 October, but put into corps reserve by Middleton.[122] During October and into November these divisions ran deception maneuvers to confuse the Germans, and also became thoroughly familiar with the terrain so as to be able to absorb a heavy thrust from the enemy should they be attacked. However, from mid-November to early December the three well-prepared infantry divisions were all replaced by two battle-weary divisions and one green division. Both the 28th Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Division, Middleton's old division from World War I, had taken heavy losses in the Huertgen Forest, and were at less than 75% normal strength. The 106th Infantry Division was just entering the lineup with no combat experience. Middleton now had about 68,000 officers and men in his corps, many weary and many uninitiated, along an 88-mile front facing about 200,000 veteran German troops who were deftly moving into position under the cover of darkness.[123]

Battle of the Bulge

[edit]Striking at 5:30 a.m. on Saturday, 16 December, the Germans achieved almost total surprise in breaking through the allied lines, beginning what is commonly called the Battle of the Bulge. The Germans launched their great attack of 1940 through the same region, with Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt in command then as he was once again in this campaign.[124] His goal was to separate the American forces from the British and Canadian forces, and take the important port city of Antwerp. By late afternoon the Germans had 14 divisions operating in the Ardennes, but this number would swell to an estimated 25 divisions, with 600 tanks and 1,000 aircraft.[125] The 106th Division, located in the most exposed positions along the corps line, and the 28th Division took the brunt of the attack. Middleton, headquartered in Bastogne, was awakened by a guard and could hear the guns from there. Throughout the day, the 106th was able to hold its position, but additional German units poured in during the night. Much of the 106th was on the German side of the Our River in an area known as the Schnee Eifel. The division's commander, Major General Alan Jones, called Middleton, concerned about his two regiments east of the river. The conversation was interrupted by another call, and then resumed. At the end of the conversation Middleton told an aide that he had given his approval to have the two regiments pull back to the west side of the river. Jones, on the other hand was convinced that Middleton had directed these units to stay, and was further convinced of this based on a written order from earlier in the day, but just received.[126] As a result of the miscommunication, the pullback did not occur, and the two regiments were ultimately surrounded with most of the men captured on 17 December.[127] While two of the 28th Division's regiments survived the German onslaught intact, the 110th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Hurley Fuller, was directly in the path of the advance. On 17 December Fuller counterattacked, but his lone regiment was up against three German divisions, and when Fuller's command post was attacked he was taken prisoner. Middleton next heard from him in April when he was released.[128] Though the 110th Regiment was shattered, the resistance given by them and other VIII Corps units greatly slowed down the German timetable.[128]

The city of Bastogne, Belgium was a hub of several major roads and became a prime target for the Germans, seeing its capture as necessary to their advance. Middleton was in continuous communication with Bradley at 12th Army Group headquarters in Luxembourg, and maintained that though Bastogne could soon be surrounded, it should be held.[129] As the Germans advanced on Bastogne, both Bradley and First Army commander Hodges recognized the threat to Middleton and had him move his headquarters. He was supposed to leave Bastogne on 18 December, but spent another night there so that he could brief his relief force, the 101st Airborne Division. Not only did that division's acting commander, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, show up ahead of schedule, but so did Colonel William Roberts from the 10th Armored Division Combat Command R (CCR), sent by Patton. Another welcome guest arriving later that evening was Major General Matthew Ridgway, commander of XVIII Airborne Corps, en route to his headquarters, but advised by Middleton to stay in Bastogne for the night to avoid capture by the Germans.[130] While Middleton and his guests slept, elements of the 101st Airborne poured into Bastogne all during the night and into the following day.[131]

Having conferred with McAuliffe at length the previous evening, Middleton left Bastogne after full daylight on 19 December, and set up headquarters in a school building in Neufchâteau, 17 miles to the southwest.[132] For the next several days, Bastogne was defended by the 101st, along with elements of CCR and some corps artillery assets that Middleton was able to supply. McAuliffe had units scattered in towns surrounding Bastogne, which bore the brunt of attacks by the Panzer Lehr Division and Second Panzer Division. At one point on 19 December, some of McAuliffe's units wanted to fall back, and McAuliffe concurred, calling Middleton for his approval. Middleton's response was, "we can't hold Bastogne if we keep falling back" and the units were ordered to stay.[133]

On 20 December, VIII Corps was moved from Hodges' First Army back to Patton's Third Army. Bastogne was being surrounded by the Germans and without adequate weather for airdrops, supplies were running low. By 22 December the Germans felt that their position around Bastogne was strong enough to send in an emissary with a note advising the Americans to surrender the city, or they would be attacked in the afternoon. McAuliffe's famous reply, "Nuts!" was sent back to the German commander. The Germans did renew their attack that afternoon, but it was muted by freshly falling snow, and a stiff American response. The next morning, 23 December, was the eighth day of fighting and the first day that the sun had emerged from behind the thick fog and clouds since the beginning of the battle. The Ninth Air Force was able to send 240 aircraft over Bastogne that day, each dropping about 1200 pounds of critically needed supplies, including artillery rounds that were delivered in the morning and used against the Germans the same afternoon.[134] Over the next three days, offensives made by the Germans were countered with responses from the Americans. In the late afternoon on 26 December the first elements of the long-awaited 4th Armored Division arrived in Bastogne, breaking the siege of the city.[135] Hitler demanded that Bastogne be taken, but even with nine divisions in the fight, the Germans were not able to break in. With the siege broken and additional elements of the 4th Armored Division coming in, Middleton stipulated that the top priority was to get the 964 wounded troops out of Bastogne and into area hospitals.[136] Despite the small opening to the city, it was clear by 27 December that the Germans were throwing their principal effort against Bastogne.[137]

In response to this renewed German thrust against Bastogne, Eisenhower released two new divisions on 28 December, the 87th Infantry and the 11th Armored.[137] These units joined the 101st Airborne Division in the corps lineup just in time for a new offensive on 30 December to shrink the bulge created in the allied line. The Americans began their attack at 7:30 that morning, which, coincidentally, was the exact time that the Germans, under General der Panzertruppen (Lieutenant General equivalent) Hasso von Manteuffel scheduled an attack of their own. The 11th Armored Division had difficulty meeting its objectives (for reasons not related to the strength of the Germans), but the 87th Division fought well in the snow, sleet and deepening cold.[138] On 3 January the new 17th Airborne Division relieved the 11th Armored Division, and the corps stretched along a crude 15-mile line due west of Bastogne, with the 101st continuing to hold the city. For the next two weeks the corps moved steadily north in heavy, sometimes even desperate, fighting, and on 16 January they met units from First Army pushing south at Houffalize.[139] Over the following twelve days the combined force pushed the Germans back eastward across the Our River, returning the Allied line to its original position before 16 December battle began, eliminating the bulge created in the Allied line on 16 December.[139]

Push across Germany and victory

[edit]

With the front restored to its previous boundary, Bradley summoned his Army and Corps commanders to his headquarters. He wanted Hodges' First Army to advance to the Rhine, while Patton's Third Army would stay put until First Army reached the river. Patton was very reluctant to hold in place, and questioned the advisability to do so. Bradley explained that all available ammunition and reinforcements would go to First Army, since two armies could not be simultaneously supplied.[140] Patton reluctantly accepted Bradley's explanation, but after that meeting he called together his three corps commanders, Manton Eddy of XII Corps, Walton H. Walker of XX Corps, and Middleton. He asked Eddy if he could ease forward and capture Trier, Walker if he could do the same with Bitburg and Middleton if he could take Gerolstein. All three commanders agreed to this, and within a few days all three had reached their objectives.[141] Middleton was then asked by Patton to take his corps all the way to Koblenz on the Rhine River, which he did, and VIII Corps reached the river before any units of First Army arrived.[141]

Once the VIII Corps was at Koblenz, Patton took most of its divisions away for an operation with XII Corps further up the river at Mainz, leaving Middleton with some corps units (mostly artillery) and a single division, the 87th Infantry. Middleton asked Patton if he could take Koblenz with the 87th, eliciting a laugh from the army commander. Middleton pressed him to let him try, and with the commander's approval he was able to take the city, which only had about 500 defenders. Most of the other German troops were on the other side of the Rhine not wanting to get trapped between the Rhine and the Moselle Rivers.[142]

Once Koblenz was captured in mid-March 1945, VIII Corps was assigned a 25-mile front from Koblenz upstream (southeast) to beyond Boppard and the famous landmark, the Lorelei. Patton then gave Middleton the 89th Division and 76th Division for the river crossing. Middleton chose to cross the river near the Lorelei where the river was narrow, swift, and flanked by steep terrain, eliciting another laugh from Patton. Middleton knew there would be little German resistance there, and he was able to get the entire 89th across in one night using inflatable rafts, and then put a pontoon bridge in place by early morning. The 87th initially attempted to cross at Koblenz but met too much resistance there, compelling them to move further upstream closer to Boppard, where their crossing went smoothly.[143] Within two days Middleton had all three of his divisions across the Rhine.[144]

In late March, VIII Corps advanced eastward through Eisenach and then across the Fulda River. Here some of Middleton's infantrymen came across the concentration camp at Ohrdruf, discovering the sickening evidence of what had transpired there. Middleton called Patton to come take a look, and Patton was joined by Bradley and Eisenhower.[145] In his diary, Patton described the place as "one of the most appalling sights that I have ever seen."[146] This was the first Nazi concentration camp to be discovered by the United States Army, and Eisenhower cabled Marshall to get a delegation from Congress over to witness and communicate what took place there. Middleton later had officials from the town come in. While every one of them denied knowing what was happening, the mayor and his wife both committed suicide that night.[147]

The VIII Corps continued its eastward advance well into the month of April, and was ordered to stop between Chemnitz and the Czechoslovakian border, where the corps would make contact with the Russians. The immediate problem was dealing with the prisoners of war. The Americans were almost overwhelmed by the number of Germans wanting to surrender to them, and despite orders to take no more prisoners, thousands of Germans filtered through VIII Corps lines at night, desperately trying to avoid capture by the Russians.[148] During the last week of April, a Russian cavalry unit made contact with Middleton. While the leaders of both the Americans and the Russians exchanged luncheon invitations, the Russians were extremely reluctant to allow any Americans across the Russian line, and their American lunch guests were taken by a very circuitous route into Russian-held territory.

"My Dear General Middleton, Again the exigencies of war have separated the VIII Corps and the Third Army. We are all most regretful. None of us will ever forget the stark valor with which you and your Corps contested every foot of ground during von Rundstedt's attack. Your decision to hold BASTOGNE was a stroke of genius. Subsequently, the relentless advance of the VIII Corps to the KYLL River, thence to the RHINE at its most difficult sector, resulting in your victorious and rapid advance to the MULDE River, are events which will live in history and quicken the pulse of every soldier. Please accept for yourself and transmit to the officers and men of your command my sincere thanks and admiration for the outstanding successes achieved. May all good fortune attend you. Very sincerely,"